In Lagos State, Nigeria’s sprawling megacity, sexually abused children from poor homes endure a second betrayal, a justice system riddled with extortion, indifference, and impunity. As anguished families wrestle with endless delays and crushing costs, perpetrators roam free. In this investigation, Christiana Alabi-Akande unveils how poverty silences the vulnerable, transforming justice from a basic right into a luxury only a few can afford.

On Wednesday, 30 September 2020, Favour Okechukwu, 11, was gang-raped to death in Ejigbo, a low-income suburb in Lagos State.

The victim’s family had expected swift justice, but almost five years later, it remains a mirage.

Frustrated by her failure to secure justice for her late daughter, the deceased’s mother, Ruth Okechukwu, a petty trader, surrendered to her grief, clinging to God for justice.

“The police made us believe they were working on the case and promised to get to the root of the matter, but nothing was done,” she told DevReporting.

From the transportation of Favour’s remains for autopsy to the endless visits to different police stations, the deceased’s relatives were responsible for every dime. Even as they grieved, they realised that seeking justice comes with a financial burden.

With teary eyes, Mrs Okechukwu narrated that: “My husband took her body from Isolo General Hospital to Ikeja for the autopsy on 18 November 2020 because we were told that the doctor could not go to Isolo. The mortuary attendant helped us arrange for an ambulance. We paid for the ambulance and funded the entire process. The autopsy process lasted from morning until night.

“We were assured the result would be ready within two to three weeks. But we never saw the result. The doctor claimed to have submitted it to the police, yet the police said they never received it. We were also kept in the dark about the outcome of the forensic test conducted at the scene of the rape. The suspects who were reportedly arrested were later released”.

When contacted by DevReporting, the lawyer in charge of the case, Alex Ishogba, explained that the Magistrate Court, sitting in Oyingbo, Ebute Metta, initially remanded the suspects in Kirikiri correctional centre (prison) and sought legal advice from the Directorate of Public Prosecution (DPP).

The lawyer, engaged by the poor family, said when the DPP reviewed the case file sent by the Lagos State Police Criminal Investigation and Intelligence Department (SCIID), Yaba, they found major gaps – key documents like the sperm test results, autopsy report, and fingerprint evidence linking the suspects to the victim were missing. With no evidence in the file, the DPP advised releasing the suspects. “The magistrate court then released them based on this advice.”

“Before the legal advice was released, I went to the DPP and I was told that the police messed up the case, because they didn’t put the medical reports and all the evidences in the file,” the lawyer added.

In order to get justice for the family of the victim, Mr Ishogba said he took the case to the Federal High Court in Ikoyi to sue for the enforcement of fundamental human rights. However, the court ruled there was not enough to link the suspects to the case.

For many poor parents of sexually abused children in Nigeria, God becomes their last resort when the criminal justice system, meant to protect them, ends up extorting and shielding the children’s abusers, forcing countless children to carry invisible scars, wounds etched by sexual abuse at the hands of those meant to protect them.

In the absence of justice

A 2020 study titled “Justice Through the Lens of Survivors,” conducted by the Domestic and Sexual Violence Response Team (DSVRT) revealed that when justice is well administered to survivors, it could give a sense of relief and closure.

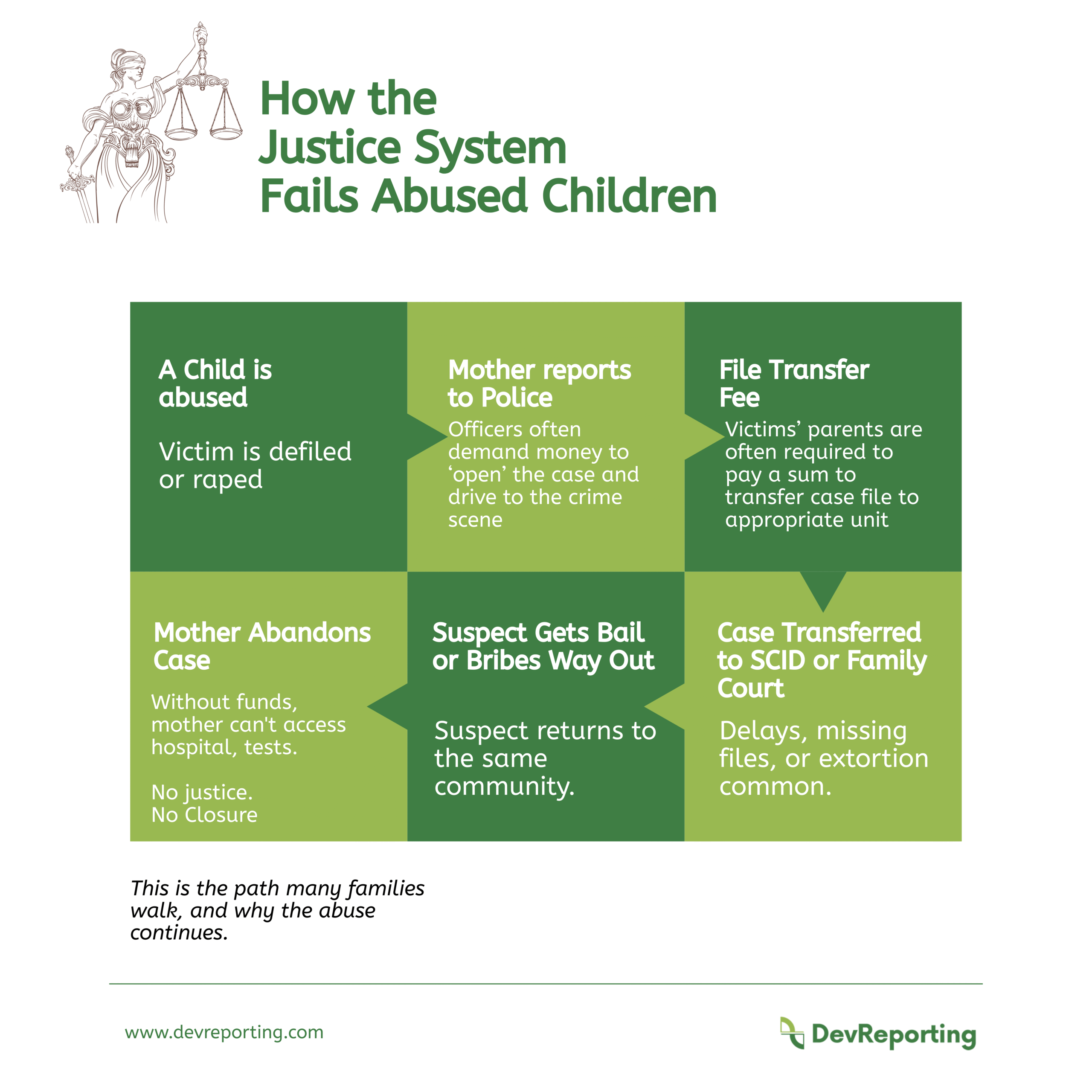

But findings by DevReporting revealed that the path to justice is littered with costs that many poor families cannot afford. They range from police ‘mobilisation fees’ to payment for medical reports, chartered vehicles and case entry fees, among others.

As a result, many who cannot afford to bear the financial burden or who get frustrated by endless court adjournments and delayed judgments, give up and abandon their cases.

Such failures threaten progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 16.2, which seeks to end all forms of violence against children.

However, findings by this newspaper reveal that the Lagos State Government supports the Police Gender Unit in the state financially to investigate these kinds of cases and get justice, without burdening relatives of abused children with incessant demands for money.

The Police Gender Unit is the central police unit in Lagos State Police Command, where most sexual violence cases are transferred to from divisions for further investigations before being charged in court.

Ugly trend

Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) is a silent health emergency that goes unnoticed, grossly under-reported and poorly managed, as very young children rarely have the vocabulary to describe what happened. Perpetrators exploit this vulnerability, committing their crimes under a culture of silence and stigma.

A 2024 UNICEF data revealed that 370 million (one in eight) girls and women alive today globally experienced rape or sexual assault in childhood, while 240 to 310 million (one in eleven) boys and men experienced rape or sexual assault during childhood. While children suffer different forms of violence, sexual violence is said to leave scars that last a lifetime.

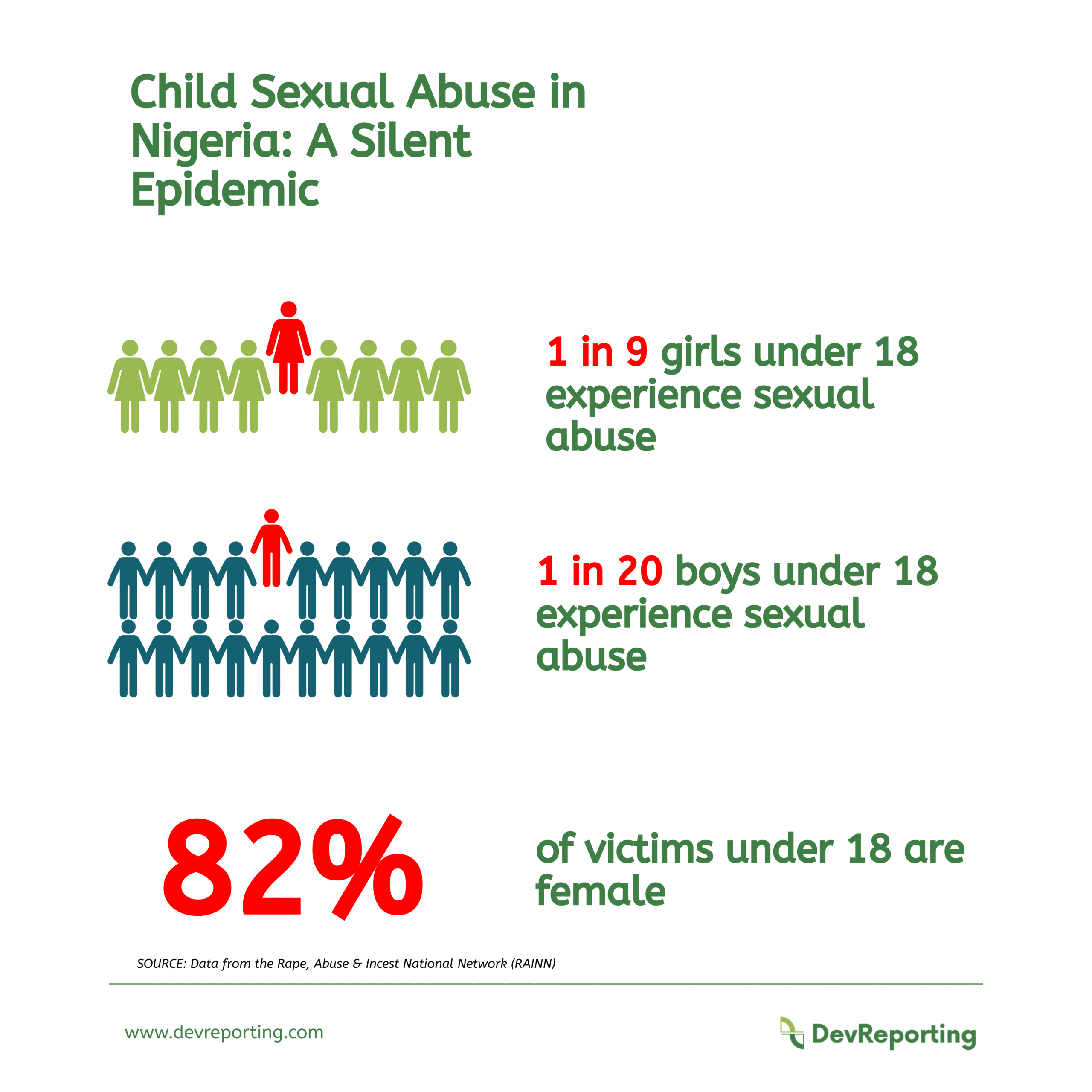

The prevalence of child sexual abuse in Nigeria is alarming, as one in nine girls and one in 20 boys under the age of 18 experience sexual abuse or assault, while 82 per cent of all victims under 18 are female, according to a data from Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), an international nonprofit anti-sexual assault organisation.

During the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, the Nigerian Police recorded about 717 cases of rape and defilement of minors across Nigeria. Late Favour was one of them.

About 799 suspects were arrested, 631 cases conclusively investigated and charged in court, while 52 other cases were left under investigation, as the then Inspector-General of Police, Mohammed Adamu, blamed the surge in the number of cases at the time on COVID-19 restrictions.

The federal government declared a state of emergency on sexual and gender based violence in all 36 Nigerian states, an action triggered by brutal rape cases across the country.

Victims’ parents lament

Like Favour, the story of Evelyn*, another victim of sexual abuse, echoes the same pain and systemic neglect faced by many sexually abused children in Lagos State.

According to Evelyn’s mother, Esther Agbim, a tea seller at Cele Market, along Mile 2-Osodi road in Lagos, her daughter, who was 10 years old in September 2023, told her that their neighbour, Lucky Bassey, invited her into his room and rubbed his manhood on her private part.

Shocked by this revelation, Ms Agbim reported the case at the Ijesha Police Station, leading to Mr Bassey’s arrest.

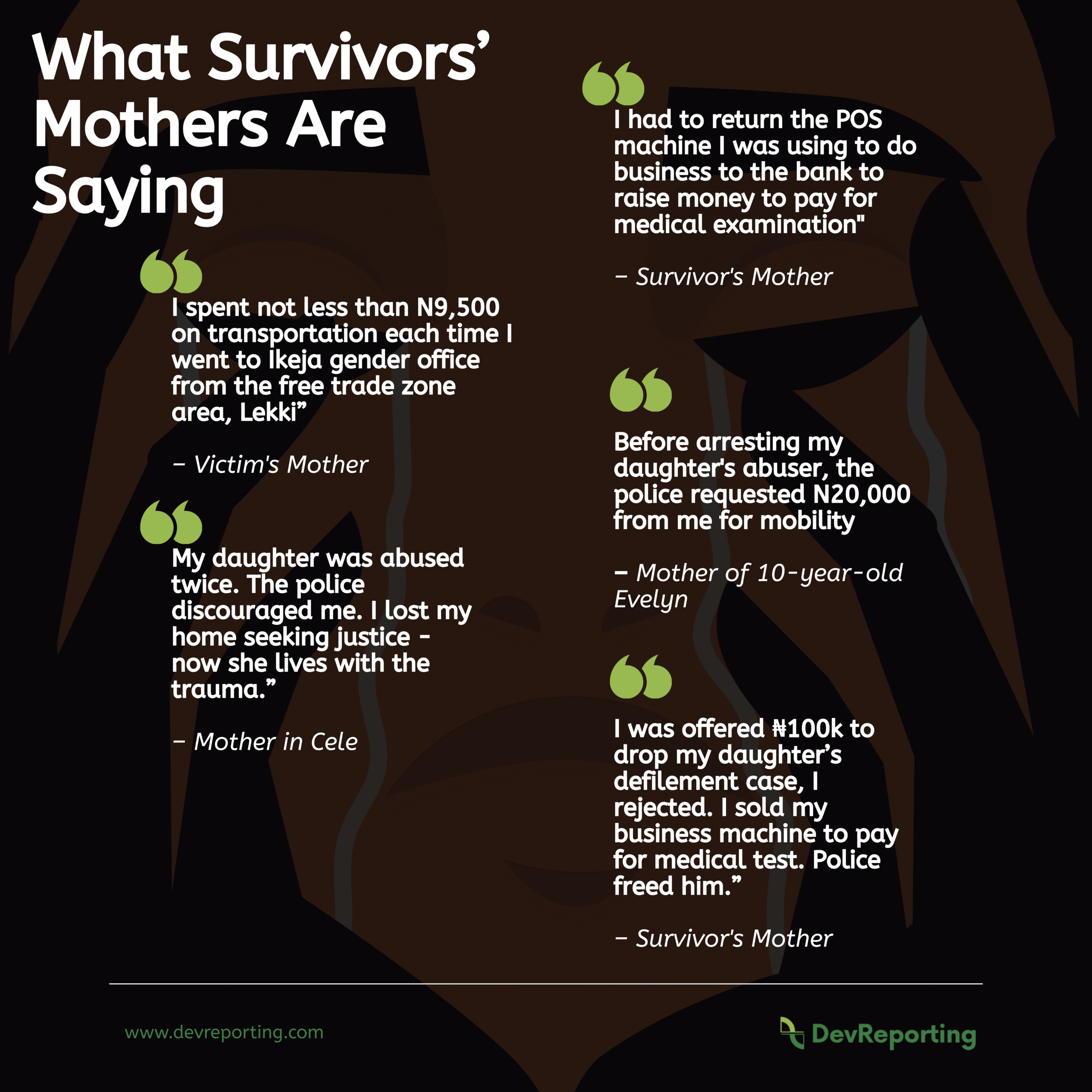

Before the suspect’s arrest, the police requested ₦20,000 from Ms Agbim for ‘mobility,’ but after pleas, she paid ₦5,000.

After a medical examination at Mirabel Centre, a sexual assault referral centre, confirmed that the girl had been defiled and sustained wounds in her vagina, some neighbours and police officers allegedly pleaded with the mother to drop the case. After much pressure and a lack of financial strength, Ms Agbim reluctantly succumbed.

Ms Agbim recalled: “The Investigating Police Officer (IPO) of the case, Madam Grace, pulled me aside and tried to dissuade me from going to the Ikeja Gender Unit. She claimed that the procedures at Ijesha Police station were no different from those at the unit, adding that many had already interceded on the perpetrator’s behalf.”

According to her, the policewoman later proposed that Mr Bassey sign an undertaking to stay away from the abused child, adding that his older brother had agreed to move him out of their compound. “I had to agree with them,” Ms Agbim told DevReporting, amid regret.

Months later, Mr Bassey accosted Evelyn for the second time in their shared bathroom and had carnal knowledge of her. The child kept silent for days after the second assault due to fear. When she finally told her mother, she said Mr Bassey covered her mouth so no one would hear her scream.

Determined not to let him escape a second time, Ms Agbim returned to the police to file another report, but then, Mr Bassey had fled, and every attempt to apprehend him proved unsuccessful.

According to Ms Agbim, each time Mr Bassey briefly returned home and she alerted the police, they would not take any action.

“Instead, I was constantly directed from one police station to another,” she said, adding that; “To worsen the situation, my landlady threatened to evict me from my apartment if I didn’t drop the case against Mr Bassey. But I have chosen not to drop it.”

She insisted that if the police had acted appropriately the first time, the second sexual assault might never have happened.

“Now, I have been ejected from my apartment, and my daughter lives with the trauma. After the incident, she would often complain of stomach pain, and at one point, vomited worms. I can only imagine the pain she endured. I know I am going through all of this because I don’t have the means to pursue justice. If only I had the money to hire the best lawyer, maybe I would get justice,” she told DevReporting.

Disillusioned with the justice system, Ms Agbim sought help from the Advocates for Children and Vulnerable Persons Network (ACVPN), a non-governmental organisation.

Addressing the possible connection between sexual assault, stomach pain, and vomiting worms, Public Health Physician, Mohammed Ibrahim, a professor, explained that when heavily infected, children in Nigeria can sometimes vomit worms, especially the common roundworm Ascaris. He emphasised that this is a recognised medical occurrence and is not related to sexual assault.

He further noted that abdominal pain can arise from many different causes, noting that, medically, its significance depends on the nature and location of the pain as well as other associated symptoms and signs.

Mr Ibrahim, however, mentioned that abdominal pain may result from sexual assault or from a variety of other causes. “The doctor can only determine the actual cause after fully examining the patient,” he added.

DevReporting contacted Mr Bassey for comments, but he did not respond to calls and many text messages sent to his known phone number on the allegations against him.

A story too many

At Lakowe community in the Ibeju Lekki area of Lagos, a mother of two, Amuanamua Overere, recounted a distressing incident involving her five-year-old daughter, Sophia*.

According to Mrs Amuanamua, Sophia was defiled by a neighbour identified as Frederick on 29 October 2023 when she was three years old. She had gone to refill her cooking gas cylinder and left her daughter at home. On her way back, she saw Mr Frederick, who was heading out to buy fish.

“He offered me one of his gas cylinders so I could boil water to bathe my baby. Later that day, unknown to me, he gave Sophia money to buy biscuits and instructed her to return the change to him. After handing him the change in his room, he made her watch a movie before penetrating her with his fingers. She returned with torn underwear and knickers, crying when I eventually found her after searching for over four hours.”

Mrs Amuanamua told DevReporting that she found her daughter crying with red and swollen eyes. “Sophia told me he bathed her afterwards,” she said.

When she reported the incident to the community leader (Ba’ale), community members pleaded with her not to escalate it, offering to refund all expenses she had incurred on her daughter’s health, but Mrs Amuanamua refused.

Upon realising that the community wouldn’t act, she reported to the Akodo Police Station on 1 November 2023, and Mr Frederick was arrested five days later. She was thereafter referred to Akodo General Hospital for a medical examination, which cost ₦10,000. This was in addition to purchasing gloves for the hospital.

She said: “I had to return the Point of Sale (POS) machine I was using to do business to the bank, so I could raise money to pay for the medical examination.

“When I returned to the hospital for the result, I was told the doctor had gone on leave. I waited for a whole month to get the result. During the waiting period, the Police released Mr Frederick”.

Mrs Amuanamua said the community later turned against her, while her landlord asked her to vacate her apartment.

“Later, a woman reached out, saying she was sent by Frederick to offer me ₦100,000 to drop the case. I asked her if she would let Frederick go free if he had abused her daughter.

Also, the Investigating Police Officer (IPO), identified as Ryan, said they granted Mr Frederick bail because I had not produced the doctor’s report in time. He shouted at me, saying I made allegations without evidence.”

Mrs Amuanamua said after she submitted the medical report to the Police, nothing was done, and Mr Frederick had disappeared from the community. She was later introduced to Harmony Advocacy Network, an NGO, and on 28 November 2023, the case was transferred from Akodo Police Station to Ikeja Gender Unit, where she got a new IPO, identified simply as Mr Kunle.

“The woman in charge of the Ikeja Gender Unit said the police needed to visit the crime scene and asked me to hire a vehicle to take them to Oshoroko. I told them I didn’t have the money and went home. Already at that time, each time I visited the gender officer from the Lekki free trade zone area where I reside, I spent nothing less than N9,500 on transportation up until December.”

Later in December 2023, Sophia’s mother told DevReporting that the Police called to inform her that they were coming to the Oshoroko community to investigate her case.

“They met with the Baale’s deputy, who assembled local women. Shockingly, my neighbour, Mummy Halimo, whose daughter was earlier playing with Sophia, denied seeing her that day. Even a boy who had earlier confirmed seeing Sophia enter Frederick’s room also denied it after he was threatened. I burst into tears as everything unravelled. Weeks later, Mr Frederick reportedly relocated, as my daughter continues to live with trauma.

“All I want is justice for my daughter,” she said amidst sobs, even as little Sophia told this newspaper that, “He touched my yansh.”

DevReporting made several calls and text messages to Mr Fredrick’s contact, but his phone was unavailable.

Many laws, yet no justice

According to sections 358 and 359 of the Criminal Code Act – Part Five, anyone who commits the offence of rape is liable to life imprisonment. Again, an attempt to commit the offence is felonious and the offender is liable to a 14-year-imprisonment upon conviction.

Also, Lagos is one of the states in Nigeria that has domesticated the Child’s Rights Act and underage persons are unfit to give consent for sexual acts. So even if it were to be proven that an underage victim gave consent, it would be regarded as rape. In such a circumstance, it is referred to as statutory rape.

Section 31 of the Act states that a person who commits an offence of ‘defilement’ (i.e sexual intercourse with a child) is liable on conviction to life imprisonment.

But five years of data trends from the DSVA indicate that children consistently account for between 30 and 42 per cent of total reported cases annually.

Meanwhile, Section 5 of the DSVA Law 2021 states that part of the agency’s functions is to coordinate immediate responses to sexual and gender-based violence. It is also meant to provide financial assistance, subject to the availability of funds, to high-risk survivors of sexual and gender-based violence for logistics to various responder agencies, case management, medical assistance, sexual assault counselling, psychosocial support, business seed grants, cost of relocation, or any other form of allowance or assistance necessary.

In his reactions, Ebenezer Omejalile, co-founder and chief operating officer of Advocates for Children and Vulnerable Persons Network (ACVPN), said the path to justice for many sexually abused children from low-income families is littered with insurmountable costs. According to him, it has become a norm that the oppressed cannot get justice if they do not know anybody to push their case.

“It is very shocking that despite the training and capacity building programmes, the police in the family support or gender unit have acquired, some of them still exhibit a high level of incompetence in the way they go about cases. A child has been defiled, yet they are subjecting her to outrageous costs. Perpetrators are always ready to pay any amount to escape being punished by the law,” he told DevReporting.

Mr Omejalile said: “Based on our encounter, some police officers want to turn themselves to law courts, prosecutors or judges. We’ve seen situations where complainants who are not accompanied to the police stations are frustrated by officers right from the ‘counter’, denying them access to the unit meant to handle their case.

“We have a case that is still ongoing in the Ikorodu Magistrate’s Court. There is a prosecutor there who is in the habit of telling the magistrate that defilement and rape cases are family matters. They are also in the habit of not letting the victims know the date for the next sitting. For most cases, they provide weekend dates. Tell me, which court sits on weekends?”.

…………………….…………………………

Editor’s Note: The second part of this report contains details of our reporter’s encounter with officers in different police stations in Lagos while trying to report sexual abuse and defilement cases. Note that names with an asterisk (*) are pseudonyms.

This report was supported by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under its Report Women! Female Reporters Leadership Programme (FRLP)

![INVESTIGATION [I]: In Nigeria’s ‘megacity,’ poverty, extortion deprive sexually abused children of justice](https://devreporting.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Opening-illustration-768x543.jpg)