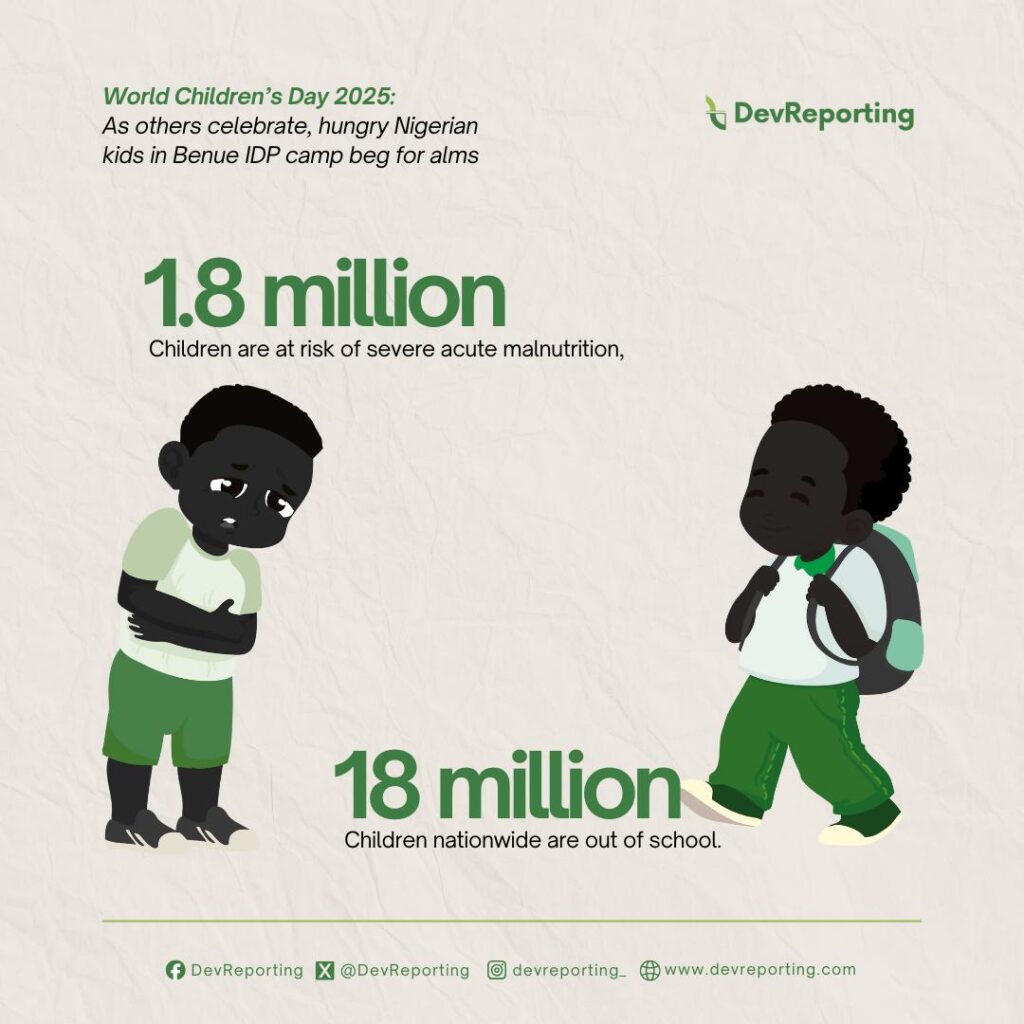

With about 18 million out-of-school children in Nigeria and 1.8 million at risk of severe acute malnutrition, the renewed violence across many states in the country worsens the plight of children. DevReporting’s recent visit to an IDP camp in Benue exposed the keg of gunpowder Nigeria now dangerously sits on. To mark this year’s World Children’s Day, Mojeed Alabi and Mohammed Taoheed report the precarious situation at the International New Market IDP Camp in Makurdi.

On a sunny noon on Saturday, 18 October, at an Internally Displaced Persons’ camp located within the International New Market, around Tamen, Abu King Shuluwa Road in Makurdi, Benue State capital, North-central Nigeria, two young girls, probably between six and eight years of age, were busy struggling to set empty pots on fire.

The whole scene felt oppressive, suffocating, and relentless, like nature’s alarm bell screaming for attention as flies swarmed everywhere, buzzing around, landing on anything. The smell hit like a wall- sharp, sour, and clinging, with a murky, sludge‑filled drainage and a faecal heap within a short distance.

“Since we were brought here around July, the toilets had already been filled up, and no one had come to evacuate them. The space in front of the unoccupied rows of shops is dedicated to open defecation and serves as our refuse dump,” said Suega Ngunna, a nursing mother at the camp.

The two girls – Theresa and Elizabeth (not real names) are friends who were united by fate as victims of the massacre that occurred between 13 and 14 June in Yelwata, an agrarian community in the Guma Local Government Area (LGA) of Benue State.

The attack claimed many lives, destroying buildings, schools, healthcare services, and even access to places of worship. While authorities claimed a death toll of 45, locals told DevReporting it could be more than 100.

Theresa and Elizabeth are among more than 2,000 households ‘dumped’ at the makeshift camp by the Benue State Government after they had been sacked from their village by marauding bandits.

Hunger in camp

Like many in the camp, the girls had not taken their breakfast on this day; yet, it was almost time for lunch. They said their parents had gone out earlier in the morning to work for families within the neighbourhood to raise money for food.

These girls’ age mates were also outside the camp begging for alms, as many of them claimed they were hungry and needed help.

Not long after, the government officials arrived with a truckload of akpu, a staple Nigerian food made from fermented cassava, and families trooped out en masse to queue for their first meal of the day.

However, many were reluctant to join the queue because they said they were tired of eating the same food almost everyday.

After four months in the camp, the girls said they were already traumatised and had no interest in many things. Schools abandoned, dreams shattered, they said life had been hard in the camp, and they were eager to return to their village to see what was left of their school, playground, and their parents’ farms, where they could eat what they loved and sing the new national anthem, which they said they had finished memorising before the violent attack.

This is exactly the fate of many of their mates scattered across the various IDP camps nationwide due to renewed violence in many parts of Nigeria.

Just on Monday, 25 female students of the Government Girls Comprehensive Secondary School, Maga town, Danko Wasagu area of Kebbi State, Northwestern Nigeria, were abducted by gunmen. The school’s Vice-Principal, Hassan Makuku, was violently shot dead while reportedly resisting the attackers.

What statistics show

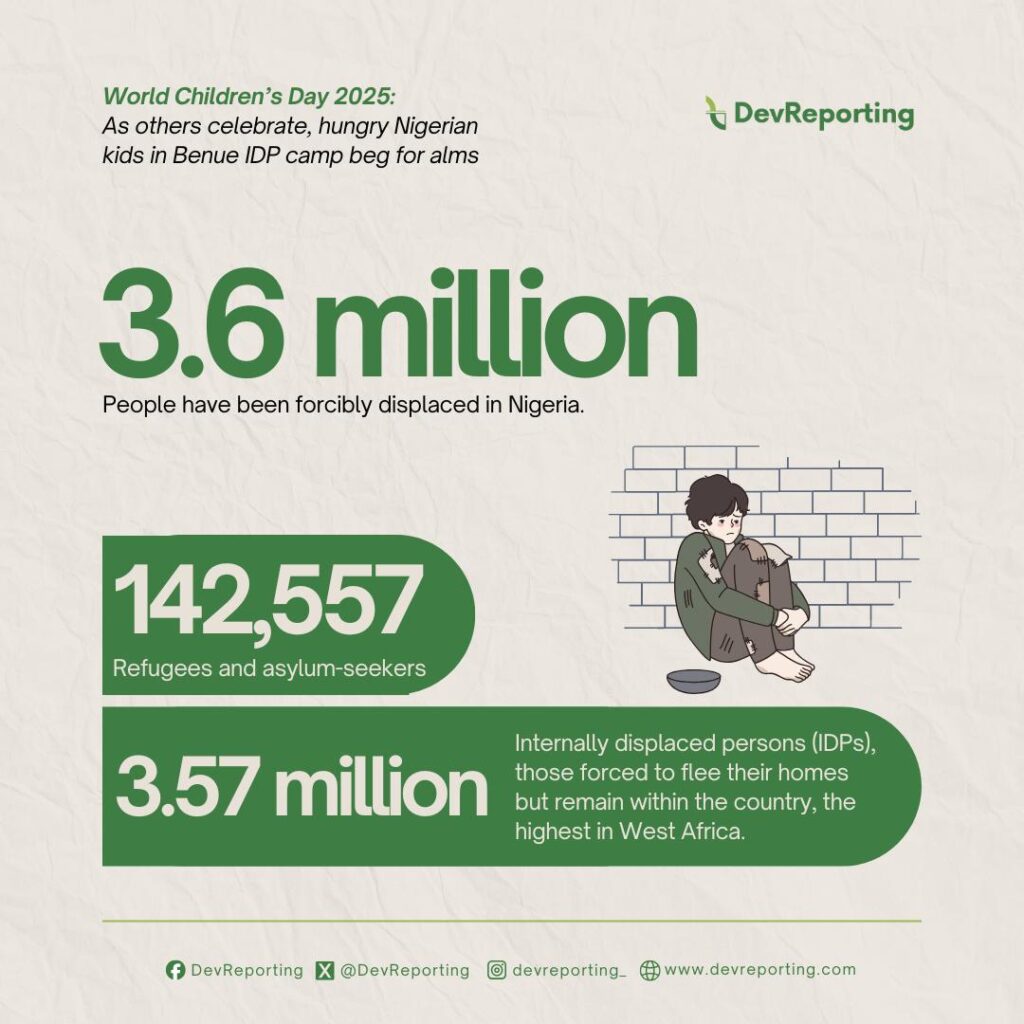

According to the Moving Minds Alliance (MMA), a global multi-stakeholder coalition advocating for the integration of Early Childhood Development (ECD) into every crisis response, as of October 2025, Nigeria is facing a significant displacement crisis.

Quoting the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other government sources, MMA said more than 3.6 million people have been forcibly displaced in Nigeria.

“This includes 142,557 refugees and asylum-seekers, and a staggering 3.57 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), those forced to flee their homes but remain within the country, the highest in West Africa,” the organisation said, adding that more than half of this figure are children.

It also noted that 1.8 million children are at risk of severe acute malnutrition, and “over 18 million children nationwide are out of school, many due to conflict, insecurity and displacement.”

Nursing mothers cry out

Elizabeth Kelvin recalled when things changed, seemingly overnight. The 30-year-old had grown up farming across the sprawling Guma Local Government Area in Benue State, and the thick forests of her Yelwata community had fed her people from time immemorial.

“My parents are commercial farmers, and my siblings and I helped them. That’s how we were brought up,” she told DevReporting.

When the attackers struck in Yelwata, Ms Kelvin was pregnant. She recounted how the first round of gunshots came in the middle of the night.

“I heard faint footsteps at first. Then, gunshots and that was it – boom, boom, and boom everywhere,” she said in a muffled tone.

ALSO READ: ‘In Between Sexes’: Nigeria’s intersex community battles stigma, medical abuse

Her family and neighbours began to scamper for safety. Her husband, children, and some of his family members are without homes, too. They are among about 6,680 people currently staying temporarily at the IDP camp in Makurdi.

“We have more than 2,334 households in this camp and almost everyone has the same fading tune: hunger,” said the camp’s secretary, David Ukeyime.

Mr Ukeyime lost his wife and daughter to the violent crisis, noting that the hapless girl was butchered by the assailants.

According to Ms Kelvin, due to poor healthcare at the IDP camp, her child, now one month old, suffered what she described as a dislocation during childbirth, saying she was rushed to a hospital for a cesarean section when she was in labour.

She said the nightmare of the attack that shook her village worsened her childbirth experience.

“I am more worried for my children. The baby has a shorter leg than the other, which is swollen. Her sister, a three-year-old, could not continue school. I couldn’t become a nurse due to poverty, so I had always dreamt my daughter would follow this path. Now, I wonder how this will come into reality. This will not happen as long as the place we call home remains unsafe,” Ms Kelvin said.

Another IDP, Ngunna Suega, was pregnant when the tragedy struck her community. She said Nado, her first daughter, had alerted her of the impending danger but she dismissed the poor girl, thinking the girl was merely “sleep talking.” But the reality soon dawned on her, as their house went up in flames, and the family had to escape, stepping on butchered body parts.

At the IDP camp where she had her baby, Mrs Suega said she felt unhappy and helpless as she had to drink very salty water until the resettlement process started.

“Nobody likes the filthy odour here, but we can’t do anything about it. We know it is not healthy to live here, especially children, but we have no choice but to adapt. We are living in a critical condition as you can see,” she said in her Tiv language, almost shedding tears.

Dire situation

Dozens of women at the heart of the crisis who spoke to this newspaper said they are not certain about when things will change for the better. But one thing is clear: they want to go back home.

They chorused that if the government could establish security in their community, they would be ready to go home.

They told DevReporting that they have to work for neighbours around the camp to make ends meet while their children beg for alms around.

Grace Augustine, 20, was busy tidying up her sleeping area inside one of the shops in the camp. She packed a bunch of wrappers, which she painstakingly tied to the walls. “It is difficult to sleep or feed since I came here some months ago,” she said.

Ms Augustine, a nursing mother, said she could not get important drugs for her six-month-old baby except “Panadol” and that she has no access to immunisation. She acknowledged that the government provided a health post, saying that it is always overcrowded due to their large number of cases to attend to.

“I am a farmer and I sell my produce every five days. But I can’t even tell the state of my farm now since we were rescued and brought here. Now, I can’t even afford our basic needs here. Whenever I was given a prescription in the health centre, I would either not collect it or throw the paper away because there was no money to buy the drugs,” she narrated.

Like other residents of the camp, Katherine Vitalis, a mother of five, said most times they only eat once a day since they arrived in the camp.

She said the children no longer attend school, as the learning centre in the camp serves both adults and children, without providing a proper school experience.

“One of my children, a five-year-old, is currently weak, and they said it is due to a shortage of blood, but I couldn’t take her to a hospital to get proper care,” she explained.

Counting costs

Although vaccines have proven effective in protecting children from deadly diseases, many children in Nigeria, especially in underserved communities, are left without access.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Nigeria has the highest number of unvaccinated children on the continent, with about 2.2 million children missing out on all routine childhood vaccines in 2023 alone. While many issues are leading to this inequality, conflict-torn areas are much more affected in most developing countries, as experts warn that countless children remain on the verge of contracting preventable diseases without this access.

An Abuja-based public health specialist, Jamiu Lawal, said children who do not get vaccinated are at risk of getting infected with viruses that could cause severe diseases, disability, or even death.

“Immunisation doesn’t only protect the individual, it protects the community from outbreaks,” he said.

He added that the Nigerian government must ensure that communities are safe and open to locals to access healthcare because when “immunisation coverage drops, the diseases that are already under control may spring up again, and that is risky.”

Mr Lawal said the situation in the Benue IDP camp could heighten the risk of malnutrition, noting that the lack of a balanced diet for nursing mothers may affect exclusive breastfeeding, which further exacerbates malnutrition.

“If a mother’s diet drops, it means she will produce less breast milk, and the nutritional benefits of such will be less. Worst still, under-nourished mothers are prone to fatigue and overall maternal health,” he added.

He appealed to the government at all levels to improve security nationwide, insisting that both the health and economy of a nation depend on the security of the people.

Empty promises

The Yelwata massacre in June wasn’t the first of such dastardly acts. In fact, Nigeria’s Middle Belt region, which comprises Benue, Plateau, Kogi, Nasarawa, and Kwara, among others, is a hotbed of worsening farmer versus herder crisis, where mostly Christian farmers and mostly Muslim herders are divided over communal issues.

And like his predecessors, the incumbent Benue State Governor, Hyacinth Alia, has consistently condemned the bloody massacre, saying nothing should warrant fratricidal killings.

Mr Alia reassured survivors that the state government would constantly engage security forces, traditional rulers, and relevant stakeholders to strengthen interventions and provide lasting solutions to the attacks.

But as part of efforts to keep the happenings at various camps from the prying eyes of the public, and particularly the media, gaining access to any IDP camp in Benue State requires layers of checks and securing approvals from various authorities. It is like a horse seeking to pass through the eye of a needle.

It is worse for journalists, forcing DevReporting to deploy tactical strategies to gain access to the IDP camp after various failed attempts.

Meanwhile, efforts to obtain official reactions from the government regarding the various issues raised by the camp residents were unsuccessful, as the Chief Press Secretary to Governor Alia, Tersoo Kula, failed to respond to messages sent to him. He also did not pick up calls to his mobile phone.

Other sources in the state said they are not authorised to speak to journalists on any matter, querying how our reporters gained access to the camp.

This story was produced with support from the Moving Minds Alliance (MMA) through the Reporters for Early Age Children in Humanitarian Crisis (REACH) Network Advocacy Stories Fund.