Across Nigeria, reporters are beaten, activists dragged from the streets, and newsrooms crippled by cyber-attacks, yet state actors remain silent. Drawing on new data and first-hand accounts, this report by Mohammed Taoheed reveals how repression is tightening and why those meant to uphold the law are increasingly the ones violating it.

In May 2024, the Nigeria Police Force (NPF) invited Nurudeen Akewushola, a journalist with the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR), and Dayo Aiyetan, the organisation’s publisher, for questioning. They were detained shortly after arrival.

It took the media outlet’s alarm, and press freedom advocates amplifying concerns on social media before the police eventually released them late into the night.

“I have never been out that late before, and I could never have imagined being subjected to such discomfort simply for doing my job,” Mr Akewushola told DevReporting.

He explained that the police had invited him and his principal after he published an exclusive report that exposed how parcels of land allocated for the construction of police barracks had been illegally sold. The report also exposed how two former inspectors-general of police and other senior personnel of the force were involved in bribery.

Rather than address the findings of his report, Mr Akewushola said the police focused their interrogation on the sources for his story. Citing journalistic ethics, he declined to disclose them.

ALSO READ: Silencing the Messengers: How Niger Governor targets journalists reporting insecurity

“We relied on verified documents for that story. I expected the police to go after those we named for illegal practices, and not us, who were merely performing our duty,” he said.

Mr Akewushola added that the officers’ line of questioning reflected partiality, particularly when their superiors were implicated.

Growing culture of suppression

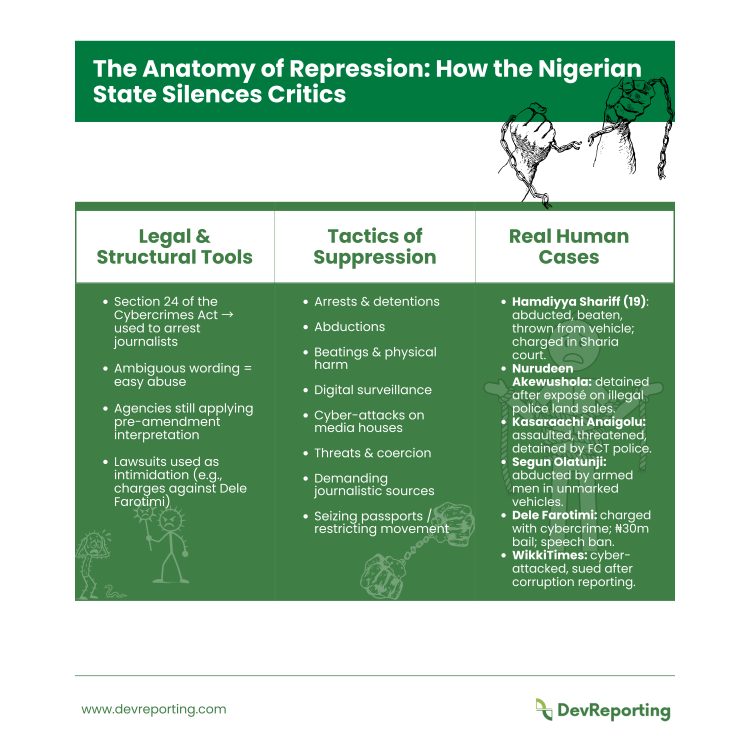

For years, Nigerian authorities have weaponised legislation to target journalists and critics. Between 2015 and 2022, about 750 verified attacks on journalists were recorded.

Security agencies routinely rely on Section 24 of the Cybercrimes Act to arrest or detain journalists, despite constitutional guarantees of press freedom and free expression.

A media freedom expert at the Centre for Journalism, Innovation and Development (CJID), Cristina Longe, said the Act has “become a tool against the press,” undermining constitutionally protected freedoms.

“Despite the amendments to remove most of the areas that could be considered crimes, it is still far from being a perfect law. Security agencies seem not to recognise the implications of the amended law and continue to arrest journalists and media practitioners based on the amended law,” she said.

Scary data

The 2024 Openness Index by CJID, published in July, revealed that Nigeria’s police, military, and state security agents continue to suppress dissent, harass journalists, and deter civic activism.

The index, a subnational assessment of press freedom and civic space in the African giant, was published in July. It ranked states based on political openness, media independence, and the safety of civic actors.

Between December 2023 and November 2024, security agencies were responsible for 48 press freedom violations.

A victim, Daniel Ojukwu, a journalist with the Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ), was abducted by the Intelligence Response Team (IRT).

Another journalist, Kasarahchi Aniagolu, was assaulted, threatened, and detained by the Federal Capital Territory’s Anti-Violent Crime Unit, Police Command, Guzape.

On 15 March 2024, about 15 armed men in two unmarked vans stormed Alagbado, the Lagos home of the then First News editor, Segun Olatunji, identifying themselves as army officers. He was coerced into following them without explanation.

Like Mr Olatunji, at least 30 other journalists were attacked while covering the #EndBadGovernanceInNigeria protests, according to the Press Attack Tracker (PAT).

ALSO READ: WSCIJ marks 20 years of accountability journalism, unveils finalists for WSAIR

One of them, Yakubu Mohammed, who works with Premium Times, was attacked in Abuja while covering a protest in the capital city. He was beaten, harassed and wounded in the head while being hit with the butt of a gun despite wearing a clearly marked press jacket.

“We should be collaborators, not enemies,” he said, noting that the assault left him unable to work or even perform routine social media monitoring essential to his role as a conflict reporter.

Corroborating this, Reporters Without Borders’ 2024 World Press Freedom Index documents the rising violence against journalists during protests, elections, and periods of political tension in Nigeria.

‘Operation work in silence’

Beyond journalists, newsrooms across the country now operate under fear, from digital surveillance to lawsuits.

WikkiTimes, an investigative outlet in Bauchi State, Northwest Nigeria, suffered repeated cyber-attacks in April, pushing its website offline.

The editor of the medium, Aminu Adamu, in an interview, said the attacks were linked to stories that certain powerful figures wanted buried.

“It’s worrying to see that WikkiTimes has become a subject of attack because of our groundbreaking investigations,” Mr Adamu said. “But we won’t stop, we are just starting, and I am happy. If our stories hold power to account and give perpetrators nightmares, then we are doing our job.”

The outlet has also faced lawsuits. In May 2024, a Nigerian legislator, Mansur-Manu Soro, sued the platform after a report alleged he used a briefcase company for dubious constituency projects worth millions of naira.

More woes for activists

Beyond newsrooms, digital activists face increasing repression in what analysts describe as a calculated attempt to silence dissent and shrink civic space in the country.

In November 2024, 19-year-old activist, Hamdiyya Shariff was abducted by armed men while on her way to collect a phone from a charging centre. She was brutally beaten, thrown out of a moving vehicle, and left with severe injuries.

Her ordeal followed a TikTok video she uploaded in which she allegedly used abusive words against the Sokoto State Governor, Ahmad Aliyu, while advocating for displaced persons in conflict-torn regions. She was later charged in a Sharia court for “inciting disturbance” and criticising Mr Ahmad. She and her lawyer, Abba Hikima, subsequently received numerous death threats.

Similarly, a human rights activist, Dele Farotimi, was charged with criminal defamation and cybercrime by a Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN), Afe Babalola, after publishing a book titled ‘Nigeria and its Criminal Justice System’. He was eventually granted bail at ₦30 million, ordered to provide two sureties, submit his international passport, and refrain from media engagements during the trial.

State actors keep sealed lips

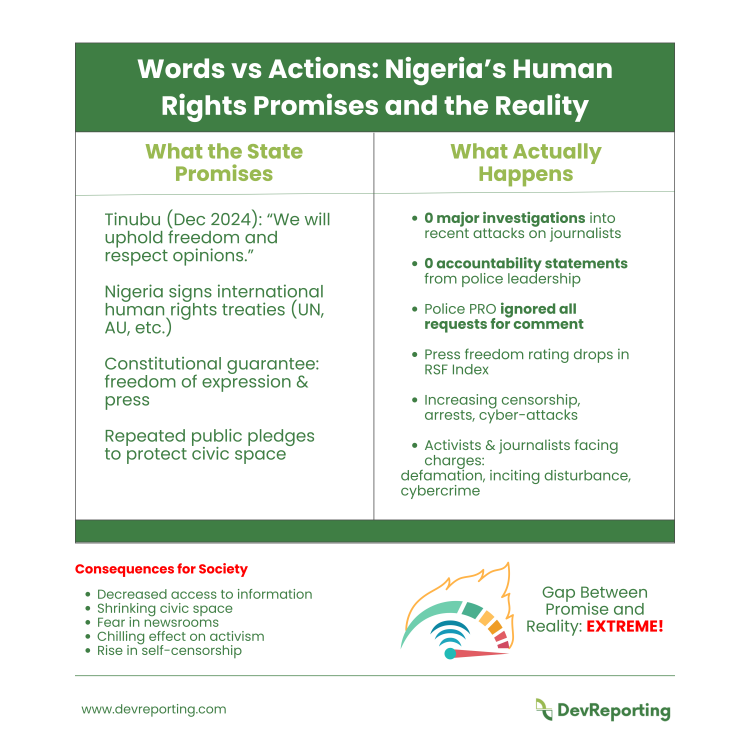

In December 2024, President Bola Tinubu pledged to uphold freedom of speech and respect opposing opinions. Yet evidence abounds that the civic space in the country continues to shrink.

Analysts, including Ms Longe, argue that infringements damage Nigeria’s international reputation, especially given its commitments to global human rights treaties.

Despite mounting calls from individuals, civil society organisations, international bodies like Amnesty International, Committee to Protect Journalists, among others, the Nigerian government has neither launched comprehensive investigations into these abuses, held those responsible to account, nor taken concrete steps to curb the trend.

DevReporting reached out to the spokesperson of the Nigeria Police Force (NPF), Benjamin Hundeyin, for comments on allegations raised against the police, but there was no response. Text messages and calls sent to his line were not returned as of the time of filing this report.

Also, the spokesperson of the Nigerian Army, Onyinyechi Anele, a Lieutenant Colonel, said when contacted, “I took over in April, after this incident had happened; therefore, I can’t say anything on it. I don’t have the facts.”

While the Army declined comments on the incident, Ms Longe warned that persistent attacks on digital rights deprive citizens of access to information and freedom of expression.

“The way out is for state actors in Nigeria to halt repressive laws, respect international human rights commitments, and create structures that safeguard journalists and activists,” she said.

This story was produced as part of Dataphyte Foundation’s project on “Addressing Digital Surveillance and Digital Rights Abuse by State and Non-State Actors” with support from Spaces for Change.