By Adejumo Kabir Adeniyi and Dr. Ola Bello

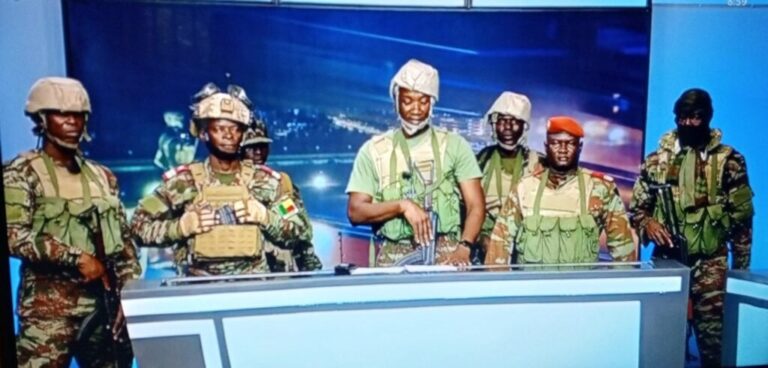

The attempted military coup in the Republic of Benin has sent shockwaves far beyond the borders of the small West African State. For Nigeria, Benin is more than just a neighbouring country; it is a country whose economy is fused with Nigeria’s, particularly Lagos State, through decades of intense commerce, daily human mobility, and deep cultural and ethnic interconnection. The failed coup feels like a crisis unfolding in Nigeria’s own backyard, highlighting the vulnerability of democratic governance in the region and serving as a wake-up call for Nigeria and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

Nigeria has watched a troubling sequence of military takeovers that began with Mali and Guinea in 2020, spread to Burkina Faso and Niger, and more recently shook Guinea-Bissau from the relative distance of the Sahelian belt. But the attempted truncation of civilian rule in Benin exposed a disturbing new reality. The implications of this moment extend far beyond Benin’s borders and directly challenge Nigeria’s regional leadership, ECOWAS’ relevance, and the future of inclusive, accountable governance in West Africa.

While the immediate danger has passed, the episode exposed underlying vulnerabilities, political tensions, governance grievances, and weakening democratic norms that created the openings the putschists attempted to exploit. But, the swift collapse of the coup in Benin suggests the public are not ready for military rule, aligning with Afrobarometer findings that Africans value democracy. In reality, most of these seizures of power have been elite-driven, opportunistic, and strategically timed to exploit institutional weaknesses, factional disputes, political miscalculations by incumbents or the meddling of external parties such as Russia, France and the United Arab Emirates, Etc.

READ ALSO: Beyond the Coup: How ECOWAS Disengagement Could Entrench Narco-Power in Guinea-Bissau

This was visible in Guinea-Bissau, where the coup was reportedly masterminded by an incumbent desperate to tighten his grip rather than any form of citizen-driven revolt. The streets of Bissau were not calling for military intervention but demanding for the full release and respect of the truncated election results.

Benin itself, once internationally praised as a model of democratic consolidation, has in recent years experienced creeping authoritarian tendencies, restrictions on political participation, and controversial electoral reforms. The coup may consolidate or collapse. Either way, the episode reflects deep structural weaknesses in governance rather than a wholesale rejection of democracy by citizens. Also, the real question is not whether Africans want democracy, but whether leaders are delivering a form of democracy that’s worthy of their trust and loyalty.

It is impossible to analyse Benin’s ordeal without acknowledging a pattern: nearly all recent coups in West Africa, save for Guinea-Bissau’s partial exception, have occurred in Francophone countries. This cannot be dismissed as coincidence. Several dynamics specific to Franco-West African political structures may be contributing to the instability. These include highly centralised presidential systems that concentrate significant power in the executive, making political contestation more volatile; historical tensions over persistent French economic, defence, and political influence; and fragilities in state cohesion shaped by colonial legacies and later political reforms.

Benin does not fit neatly into the Sahel security-collapse narrative. However, its democratic space has narrowed significantly in recent years, with controversial electoral reforms, constraints on political competition, and rising public frustration. These internal tensions provided the environment in which the coup attempt briefly gained traction before being decisively stamped out.

Failed Coup Tests Nigeria More

Benin’s failed coup is most consequential for Nigeria. Unlike other recent episodes in Mali, Burkina Faso, or Niger, Benin is intricately intertwined with Nigeria’s economic, social, and security ecosystem. This makes the attempted overthrow not merely a matter of abstract concern but a direct challenge to Nigeria’s national interests. The ethnic affinities that span the border, particularly among Yoruba, Bariba, and other communities, undercut any notion that instability in Benin can be quarantined. Moreover, the economic integration between Lagos and Cotonou is arguably one of the most intense in West Africa, with Benin functioning as a major entrepôt for Nigerian trade.

READ ALSO: Guinea-Bissau Coup: Time for ECOWAS to Change its Geopolitical Playbook

The attempted coup, therefore, tested Nigeria’s influence more directly than it tested ECOWAS. The regional body has been weakened by internal divisions, inconsistent enforcement of democratic norms, and the withdrawal or suspension of several key member states. Whether ECOWAS survives as a coherent bloc depends significantly on Nigeria’s ability to respond strategically to challenges such as this one, firmly, intelligently, and without alienating neighbours or undermining long-standing regional relationships.

For Nigeria, several red lines and strategic imperatives emerge from the Benin episode. First, Benin must not fall to external powers whose ambitions run counter to Nigeria’s security and geopolitical interests. The rapid collapse of the coup does not mean that external actors, whether mercenary groups, foreign military contractors, rival regional powers, or transnational criminal networks, will not seek to exploit the underlying vulnerabilities that the failed putsch exposed. Nigeria must remain vigilant, ensuring that no vacuum forms that could be filled by adversarial forces.

Also, communication channels with Benin must remain open at all costs. The instinct to pressure, condemn, or isolate is often counterproductive. In West Africa’s current volatile climate, quiet diplomacy and active engagement are far more effective than megaphone diplomacy. Nigeria’s goal should be to deepen cooperation with Benin’s civilian authorities while discreetly working to strengthen the country’s institutional resilience. Maintaining dialogue also ensures that Nigeria continues to shape outcomes rather than watching from the sidelines.

While Nigeria possesses considerable economic leverage over Benin, this should remain implicit and never explicitly threatened. The temptation to weaponise economic interdependence, especially in moments of political uncertainty, must be avoided. Such coercion could harden attitudes in Cotonou, breed nationalist resistance, and push Benin toward external alliances that may not align with Nigeria’s long-term interests.

Additionally, Nigeria must understand the structural limits of Benin’s own defensive posture. Benin’s far smaller economy is fundamentally dependent on re-export trade into Nigeria, including both official commerce and illicit trafficking networks. The junta’s border closure, even if only momentary, highlighted the unsustainable nature of any long-term attempt to sever economic ties. This reality strengthens Nigeria’s position in managing post-coup stabilisation efforts, reinforcing the logic of engagement rather than confrontation.

Fluid Situation With Clear Lessons

While the coup failed, its implications remain profound. It revealed how fragile the region’s democratic structures have become and how urgently West African states, especially Nigeria, must rethink their strategy for safeguarding responsive, accountable governance. The fact that Benin’s democratic order endured this stress test should not lull anyone into complacency. A coup does not have to succeed to inflict damage. It merely has to be attempted to reveal vulnerabilities, embolden opportunists elsewhere, and raise questions about the durability of democratic norms.

Africans remain strongly committed to representative governance, even when their democracies fail to deliver. The problem is not that citizens prefer juntas; it is that the institutions meant to uphold democracy have repeatedly failed to live up to their promise. Benin’s experience should therefore be interpreted not as evidence of a population yearning for military intervention, but as a reminder that democracy in West Africa is dangerously teetering on weakened institutional foundations.

Stable democracies do not emerge by accident, they are secured through consistent engagement, strategic diplomacy, and a recognition that regional security begins at home. Benin’s failed coup is a warning that the next domino can fall anywhere. It is also a chance for Nigeria to reaffirm its role as a stabilising anchor in a region drifting into dangerous uncertainty.

………

Adejumo Kabir Adeniyi is a senior researcher at Good Governance Africa-Nigeria. He is an expert with many years of experience in community development work and governance accountability sector. Before joining GGA, Adejumo worked at Premium Times and HumAngle Media, two of Nigeria’s biggest newspapers specialising on conflict and accountability reporting.

………

Dr Ola Bello is the Executive Director for Good Governance Africa (GGA). He has extensive experience in mining governance and economic transformation. He has been a member of the Technical Working Group for the implementation of the African Mining Vision since 2011.