Media professionals have raised alarm over the rising use of surveillance technologies to monitor, intimidate, and silence journalists across Africa, calling for bravery, stronger laws, and collective action to defend press freedom.

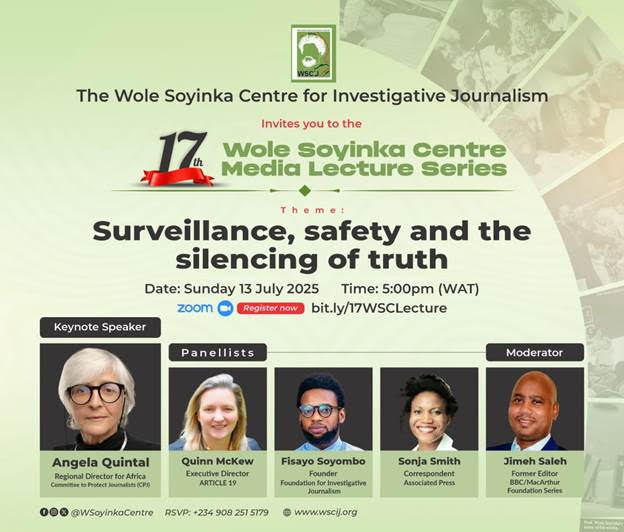

At the 17th annual media lecture organised by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ), themed “Surveillance, Safety and the Silencing of Truth,” media experts drew attention to the rising threats facing press freedom and the shrinking space for civic engagement.

The lecture held in commemoration of the 91st birthday of Wole Soyinka, a professor, Africa’s first Nobel Laureate in literature and grand patron of WSCIJ, brought together prominent voices in journalism, policy, and civil society.

This year’s edition featured the Africa program coordinator of Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Angela Quintal, as the keynote speaker. Ms Quintal brought her extensive experience in media advocacy to the discussion, particularly on how surveillance technologies are reshaping the practice of journalism in Africa.

Other panellists included the Executive Director of ARTICLE 19, Quinn McKew; Founder, Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ), Fisayo Soyombo; and an investigative journalist and Associated Press correspondent, Sonja Smith.

Moderated by former editor of the BBC/MacArthur Foundation investigative series, Jimeh Saleh, the lecture drew a diverse audience of journalists, editors, media owners, government representatives, diplomats, civil society organisations, donors, and other stakeholders to engage in a meaningful conversation about the state of media freedom on the continent.

Each speaker contributed perspectives rooted in their work across different regions, highlighting the global nature of press repression and the urgent need for coordinated action.

Digital technologies aiding press suppression

Speakers at the event expressed concern that governments and powerful institutions are increasingly deploying sophisticated surveillance tools to monitor, intimidate, and disrupt journalistic work. They noted that while digital innovation has expanded the possibilities for storytelling, it has also opened up new frontiers for press suppression.

The founder of the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID), Dapo Olorunyomi in his opening remark noted that digital technologies are double-edged.

“This isn’t just a catchy phrase; it’s a mirror reflecting the struggles of journalists in an increasingly connected and controlled world,” he said.

In her keynote address, Ms Quintal stated, “surveillance isn’t a distant abstract, it is here and it is shaping the world we live in, across Africa and globally.”

She said, “After Nelson Mandela became our first democratic elected president in 1994, an understanding was reached between the government and the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF) that Section 205 of the Criminal Procedure Act would not be used to compel journalists to reveal their sources.

“Today, section 205 is still used not to force the journalists directly to disclose their sources, but to compel telecom companies to hand over journalists’ call record. This is a form of surveillance.

“Now it is compounded by spyware and digital intrusion as the government no longer needs to knock on your door, they can just reach into your phone. It’s not just the government, the private actors too deploy technology to get journalists illegally. At CPJ, we document these abuses and raise the alarm.”

Spyware is a type of malicious software designed to covertly gather information from a computer or device without the user’s knowledge or consent.

According to Ms Quintal, surveillance is dangerous because privacy is essential to freedom. She added that journalism depends on private communication and that undermining such privacy doesn’t only impact the individual but harms society.

Legal contradictions enabling surveillance abuse

Ms Quintal lamented the presence of loopholes in communication regulations that allow security agencies to access journalists’ telecom data without warrants.

Citing an example in Nigeria, she said, “In Nigeria, police have repeatedly accessed journalists’ telecom data to track and lure journalists into arrest in retaliation for their work. They do this without warrant, permitted by loopholes in communication regulations.

“The constitution of Nigeria safeguards privacy, yet the legal framework contradicts this. We actually raised these concerns in a letter to President Bola Tinubu just about three months after he assumed office, yet, there has been no effort by authorities to implement the necessary reforms that would safeguard journalists from such surveillance.”

She submitted that robust legal protections are becoming more important as tools for surveillance keep getting more sophisticated and invasive.

In her remarks, the Executive Director of ARTICLE 19, Quinn McKew noted that repressive regimes are increasingly relying on cybercrime, anti-terror, and national security laws to legitimise the monitoring of journalists.

She added, “These legal tools are increasingly used as a form of transnational repression, making it unsafe for journalists not just domestically, but globally.”

Female journalists face gendered surveillance

An investigative journalist and Associated Press correspondent, Sonja Smith, described how women in the profession are often subjected to additional layers of harassment and intimidation.

“Women journalists are not only surveilled but often subjected to slut-shaming, sexual threats, and online harassment. These attacks are not incidental; they are systemic,” Ms Smith said.

She further described the psychological toll of constant monitoring, both online and offline, noting that “many women journalists carry invisible trauma from being constantly watched, harassed, and attacked. We need to design something specifically for women journalists.”

The Executive Director of WSCIJ, Motunrayo Alaka, underscored the social impact of these threats, saying “surveillance is constituted and intentional, so we need to collaborate more to treat this as an attack on society.”

Role of the public in resisting abuse

Panellists at the event argued that the public must be made to understand that surveillance targeting journalists is ultimately a threat to everyone’s right to know.

The founder of the Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ), Fisayo Soyombo, said the issue must be reframed to resonate with the public. “It all tilted in their favour. My final note is that 90 per cent of journalists work in and out.

“The public need to know their rights, making them see this as an attack on them rather than on journalists,” he said.

Similarly, Mrs Alaka stressed that the protection of journalists must be viewed as a duty of both the government and citizens.

“There is a need to emphasise that the role of government is to protect journalists and members of the public,” she stressed.

Collective action, stronger laws, bravery needed

The panellists concluded that surveillance has become more invasive, and only strong legal protections and collective action can provide safeguards.

Ms Quintal cited the Botswana example, where local and international pushback forced the government to revise a proposed surveillance bill.

She reiterated that “journalists cannot do their work without secure private communication. They cannot build trust with sources; they cannot hold power to account.

“The abuse of surveillance is particularly insidious because it frequently occurs in secret. That’s why we must expose it, talk about it, and resist it. All of us together.”

Echoing the same, Ms McKew warned that “smart cities sound progressive, but they are built on surveillance infrastructure, often paired with AI to create a state of constant monitoring.”

The moderator of the event, Mr Saleh, steered discussions on how journalism is increasingly under pressure not only from authoritarian governments but also from commercial interests and inadequate institutional support.

Mr Soyombo added that there is a need for journalists to be brave in the discharge of their duties, saying, bravery is an essential trait of an investigative reporter.

He encouraged journalists to know where to draw the line for their own safety when undertaking undercover reports.

Centre renews commitment to press freedom

Since its inception in 2009, the WSCIJ has used its annual lecture series to promote press freedom and civic accountability in Nigeria.

This year’s edition again emphasised the need for proactive measures to defend independent journalism.

Mrs Alaka noted that the theme of this year’s event was deliberately chosen to reflect the hostile environment in which many journalists now operate. “These threats deserve more attention in global conversations about democracy and civic space.

“As surveillance grows more sophisticated and institutionalised, the need for urgent reforms and protective policies becomes even more critical.”