This report examines a pattern of harassment, intimidation and abuse of power by Governor Bago against journalists who report on insecurity in Niger State.

By Adebayo Aare

On 31 October 2024, a retired civil servant, Yakubu Dada, and his wife were kidnapped by bandits on the Kontagora-Minna road. The bandits, who initially demanded N10 million, raised the ransom to N100 million after Mr Dada’s two other wives sold their home and other property to raise the initial amount demanded.

On Wednesday, 7 May, at the commissioning of the permanent North‑Central Zonal Office Complex of the National Centre for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons (NCCSALW), in Minna, the state capital, Ibrahim Ndamitso, a freelance journalist with the BBC, who as of then was a freelance reporter for Channels TV, asked the governor what the state was doing to rescue Mr Dada from the bandits.

Angered by Mr Ndamitso’s question, the governor accused him of working with the bandits, saying the journalist could not have known about the kidnapping case if he were not working with the bandits.

Many national newspapers reported the story, but the governor claimed he was unaware of the kidnapping and directed the commissioner of police to take the journalist into custody and profile him.

“The national dailies already reported the story. It was already public information, so there was nothing special about it. It wasn’t an intel or so, it was general information,” Mr Ndamitso said in an interview with PREMIUM TIMES.

“At the police headquarters, they requested some personal details, including my phone numbers, address, my account numbers, and date of birth, and I gave them all because I have nothing to hide. I have a legitimate means of earning a living. I’ve never been involved in crime, so I made everything available, and that’s all.

Governor threatens

The governor later directed the commissioner of police to bring Mr Ndamitso to his office.

“He met us at the lobby, not inside his office. The chief press secretary was there, the commissioner of police, his security aides and media aides were also there. All he said was a repetition of the things he had said earlier. He actually said I hated him. He then used some words that were threatening.

“He said I was reckless for asking him about insecurity, and if I keep tracking security issues, I can get killed. But when the commissioner of police tried to interject, he quickly retracted the statement and said he didn’t mean that he would kill me, but just telling me that my life is also at risk,” Mr Ndamitso told this reporter.”

ALSO READ: WSCIJ marks 20 years of accountability journalism, unveils finalists for WSAIR

Before the incident, Mr Ndamitso said he had been denied access to the state government secretariat, despite being an accredited correspondent at Government House. He believes the denial of access stemmed from his consistent habit of asking the governor critical questions about governance in the state.

“I always ask hard questions because I believe that’s the way to ensure accountability in governance. I have always been like that. I did the same with previous administrations,” Mr Ndamitso recounted.

Mr Ndamitso’s case was one of many incidents of intimidation and harassment of journalists by the governor.

Journalist questioned for reporting bandit attack

On Sunday, 1 December 2024, Governor Bago and his entourage missed their way during a tour of rural communities in the Niger North Senatorial District to inspect ongoing projects. They strayed into a terrorists’ enclave on the outskirts of the Igade (Mashegu LGA) and Bangi (Mariga LGA) axis.

Multiple sources, including those briefed by people on the governor’s entourage, told PREMIUM TIMES that tragedy almost befell the team when they drove into a terrorists’ enclave while heading back to Kontagora.

Prestige FM first reported the incident in Minna in December 2024. A few hours after the report was aired on the radio station by Yakubu Bina, a freelance journalist with the radio station, operatives of the State Security Services (SSS) raided the station’s premises in search of Mr Bina, but missed him. The secret police later invited the journalist for questioning.

“I went to the SSS office around eight in the morning,” Mr Bina told PREMIUM TIMES by phone, adding the operatives grilled him for over five hours until around 2 p.m.

Mr Bina said he could have been detained but for the intervention of his colleagues at the correspondents’ chapel and the leadership of the state’s branch of the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ).

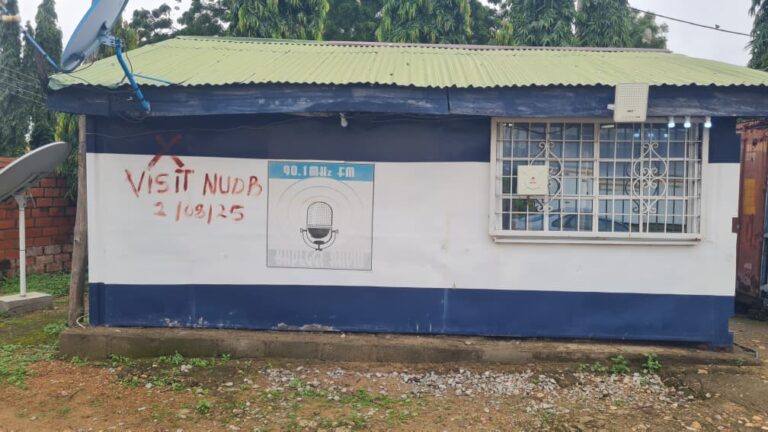

Governor Bago orders shutdown, demolition of Badeggi FM

On 1 August, the governor ordered Badeggi Radio 90.1 FM in Minna to be shut down and have its licence revoked.

In a viral video widely circulated on the internet, the governor was seen accusing the radio station and its owner, Shuaibu Badeggi, of inciting violence and fuelling insecurity in the state.

Mr Bago claimed that Mr Badeggi’s utterances were treasonous. He said his government would write to the Minister of Information to formally complain about Mr Badeggi’s alleged “anti-peace” and treasonable incitement of the public against the government.

He also directed the Commissioner of Homeland Security, Mohammed Bello, and the Commissioner of Police, Adamu Elleman, to shut the radio station and have security operatives profile its owner.

Carrying out the governor’s directives, officials from the Niger State Urban Development Board (NUDB) visited the radio station in Minna on Saturday, 2 August, at approximately 11:36 a.m. and marked it with red paint.

After the governor’s clampdown on the radio station was reported by the media, various media outlets and human rights organisations condemned the development as an abuse of state power and executive overreach, calling for the immediate reversal of the order.

The Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID), in a statement by its Deputy Director of Journalism Programme, Busola Ajibola, noted that the governor has no constitutional powers to revoke the license of any media organisation, as such powers rest exclusively with the National Broadcasting Commission (NBC). The NBC is the federal agency responsible for regulating the operations of broadcast media organisations in Nigeria.

Radio Station received no official complaint

The manager of the radio station, Aisha Shuaibu-Badeggi, later told this reporter that it had not yet received any information from the NBC concerning the governor’s complaints.

She stated that the station had no issues whatsoever with the state government before the governor’s outburst.

“They have never logged any complaint against us about any of our programmes. We believe we have had no problems with the state government as we have always upheld the highest principles of our job,” she told this reporter.

Mrs Shuaibu-Badeggi could not understand the governor’s anger against reporting insecurity in the state.

“When bandits attack any community, and the people are unable to report directly to the state government, we often put a phone call to them on our programmes and ask them to share their experiences and also let the public know how they want the government to help them, because that is the way we can help them,” she said.

The station last aired such programmes in the third week of June, following a report of an attack in Mariga Local Government Area of the State.

Niger is one of the many states with severe security challenges, including banditry. The attacks by various armed groups have led to the killing of hundreds of people, the kidnapping of thousands of others, and have left residents of many communities in the state homeless and living in IDP camps.

According to Nigeriawatch.org, Niger State recorded at least 40 incidents of insecurity between January and August 31, claiming at least 608 lives.

Many victims of the attacks have been forced to flee the state or seek refuge in other parts of the state that are less troubled.

High cost of journalism in Niger State

PREMIUM TIMES interviewed many journalists working in Niger State. All complained about the climate of fear and intimidation caused by Mr Bago’s actions against journalists.

The Chairman of the NUJ in the state, Abu Nmodu, stated that the union had intervened on several occasions to protect journalists from harassment by the state government.

Mr Nmodu expressed concerns over executive overreach in the state.

“I think it could be because there’s no proper understanding of the relationship between the government and the media on the part of the state government,” he noted.

Mr Ndamitso said he stopped attending events that had the governor in attendance following the encounter.

“You seek the opportunity to ask good questions, but that is no longer possible. It has become harder to do serious stories,” he said in resignation.

For Mr Bina, his family was thrown into fear and confusion when he was summoned by the secret police for questioning. Mr Bina, who is the chairman of the correspondent chapel in the state, noted that the environment in Niger is unsafe for journalists.

“The whole situation is demoralising. As I speak with you, I have investigative stories that I’m supposed to pursue, but I cannot do the stories for fear of attack. My wife has asked me to stop journalism because of her fear for my life.”

Press Freedom Violations in Nigeria

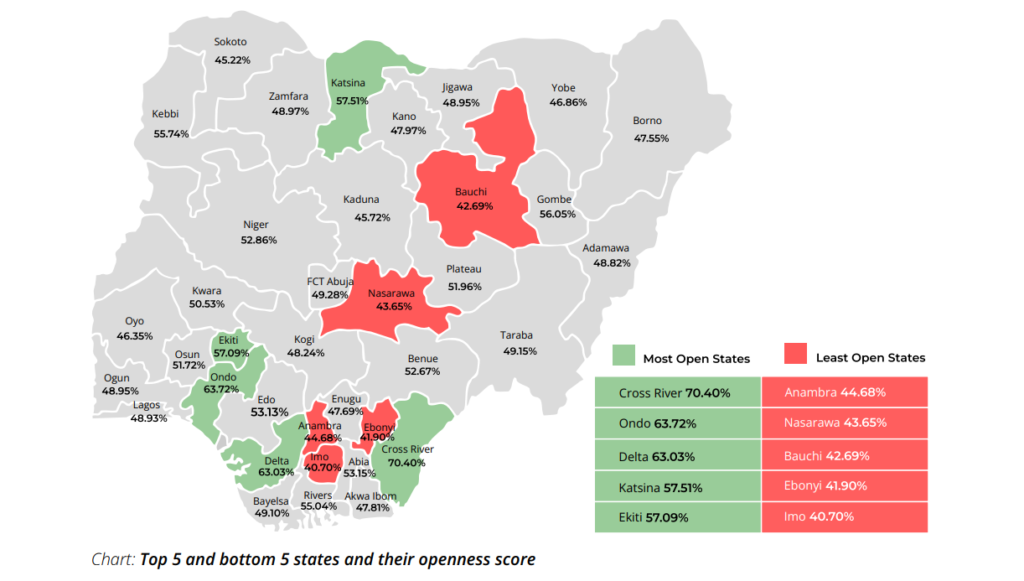

The CJID’s 2024 Openness Index ranked Niger 11th in the enablement of press freedom and civic space in Nigeria.

The index, the first subnational assessment of press freedom and civic space openness in Nigeria, ranked the 36 states of the federation and the FCT based on seven key metrics, including the political environment, legal framework, economic pressures, socio-cultural context, journalistic principles, treatment of journalists, and gender inclusion.

The index, published in July, measured political openness, media independence, and the safety of journalists and civic actors at the local level nationwide.

Imo ranked as the worst-performing state on the index.

With an overall score of 52.86 per cent, Niger State was classified as an Average Enabler of press freedom and civic space, indicating that the state is neither severely repressive nor exceptionally free for journalists to operate in.

However, there is a significant area of concern in the “Gender Factors” metric, where the state scored 46.36 per cent.

Furthermore, Niger is one of the 16 states that have not domesticated the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act or enacted similar transparency mechanisms. However, the Supreme Court ruled in April that the federal FOI Act applied to all states and local governments in Nigeria.

Another challenge is the economic environment for the media, with the state scoring 33.97 per cent on “Economic Factors,” indicating financial viability challenges and pressures affecting media independence.

The CJID openness index paints a worrisome picture of the state of press freedom in the country. This is further corroborated by the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, which ranked Nigeria 122, a ten-point decrease from its 2024 ranking.

Furthermore, CJID’s Press Attack Tracker (PAT) documented 64 cases of attacks against Nigerian journalists between January and October. The Press Attack Tracker is a civic technology tool that tracks, verifies and documents incidents of press freedom violations in West Africa.

The PAT data shows that Journalists continue to work under unfavourable conditions characterised by fear of intimidation, harassment, arbitrary arrest and increasing legal harassment, especially strategic lawsuits against public participation, with security agents and state actors being the major perpetrators of attacks.

Badeggi FM, others fight back

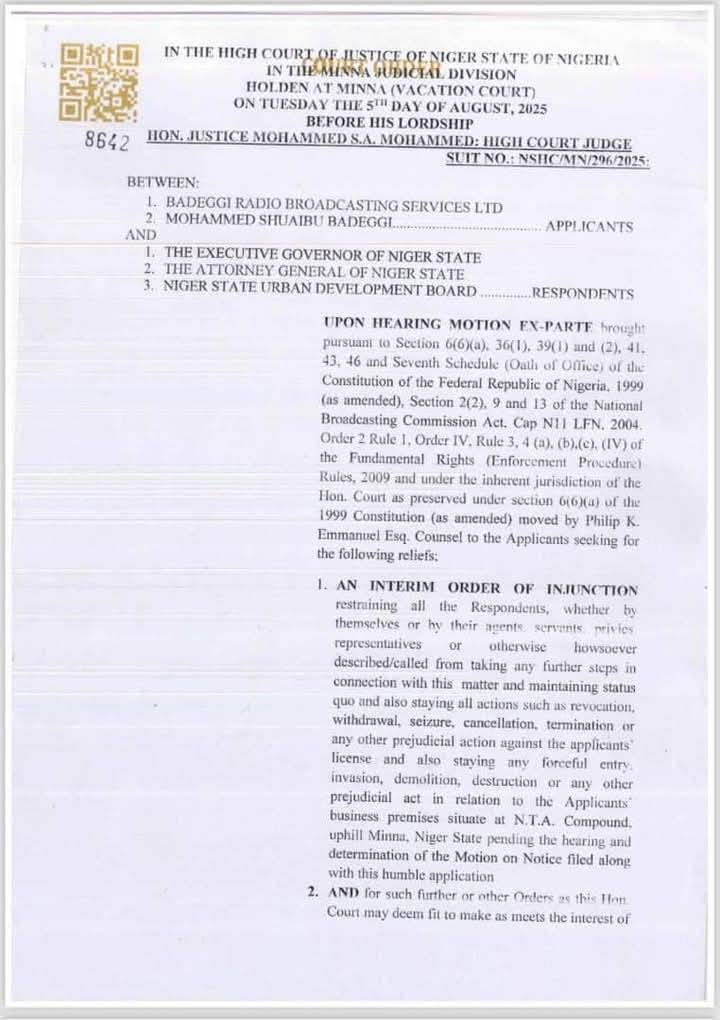

On 5 August, Badeggi FM filed a lawsuit against the Niger State governor and the Niger State Urban Development Board at the State High Court, praying the court to halt the government’s implementation of the governor’s orders until the case is decided.

In response, the court issued an interim injunction restraining the state government and its agents from taking any further action against the radio station.

This interim order was intended to allow Badeggi FM to operate freely, without interference, harassment, or intimidation from the Niger State Urban Development Board pending the determination of the case.

The government later opted for an out-of-court settlement of the case. The government’s lawyer, Jacob Usman, announced this at a hearing in the case on 11 August.

SERAP, NGE Sue Governor Bago, NBC

On 8 August, the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) and the Nigerian Guild of Editors (NGE) filed a lawsuit against Governor Bago and the NBC over “the ongoing intimidation” of Badeggi FM Radio in Minna, along with the threat to shut down the station.

In suit number FHC/L/CS/1587/2025, filed at the Federal High Court, Lagos, SERAP and NGE asked the court to determine “whether by Section 22 of the Nigerian Constitution 1999 (as amended) and section 2(1)(t) of the NBC Act, the NBC has the legal duty to protect Badeggi FM from the ongoing intimidation from the governor.”

The legal secretary of the International Press Institute (IPI) Nigeria, Tobi Soniyi, also described the actions of the governor as condemnable, adding that the right step the governor ought to have taken for media reports that the government finds inaccurate is to issue a rejoinder and state the correct position, not to shut down media houses or arrest journalists.

He urged the governor to be more tolerant towards the media and act as a listening government.

“Rather than accusing journalists of being criminals, the government should investigate the information provided.”

Mr Soniyi also urged the SSS and police to conduct their own investigations and not become willing tools for those in authority, stressing that arresting journalists for asking questions stifles journalism and inhibits press freedom.

PREMIUM TIMES made several attempts to obtain a response from the Niger State Government regarding our findings. We contacted the Chief Press Secretary to the Governor, Bologi Ibrahim, via email, WhatsApp messages, and phone calls, but received no reply. Similarly, the Special Adviser on Print Media to the Governor, Aisha Wakaso, declined to address our questions, citing an ongoing exam. A formal letter was subsequently sent to the Governor’s Office and officially acknowledged, but no answers were provided.