As families and friends around the world gathered to celebrate Christmas on 25th December 2024, 10-year-old Emmanuella took her final breath. The little girl, known for her infectious laughter and playful spirit, had battled malaria in silence. It began as a mild fever but worsened due to lack of timely treatment.

The first hospital turned her away, unable to handle her critical condition. By the time she finally received medical attention, there was nothing more that could be done.

Her death brought deep sorrow to the neighbourhood at Mangoro area in Lagos State, turning the joyful Christmas celebrations into a time of mourning. It was indeed heartbroken for neighbours who had watched her grow.

But Emmanuella’s tragic story is not an isolated one. She’s just one of the millions of Nigerians who lose their lives to malaria each year. While this preventable and treatable disease continues to claim lives, some battle recurring bouts.

Nigerians battle persistent malaria

For decades, malaria has plagued Nigeria, claiming lives, hindering productivity, draining families’ incomes, and placing a heavy burden on the nation’s healthcare system.

A 400-level student of Lagos State University (LASU), Damola Akin, shared her painful experience with malaria in 2024.

“I treated malaria more than seven times last year, especially earlier in the year. At some point, I felt the drugs I was being given at the pharmacy weren’t as effective as I expected. So I visited the school health centre, saw a doctor, and got treated, but within two to three weeks of completing treatment, the symptoms returned. This cycle continued for a while but I kept going to the hospital to complain until I got better.”

Also, a Lagos-based banker, Kabir Ekanoye, recounted his frustrating experience with a persistent bout of malaria. He initially self-medicated, spending over N3,000 on over-the-counter drugs from a pharmacy but his condition didn’t improve.

Undeterred, Mr Ekanoye sought medical attention at a hospital, where he was diagnosed with malaria. Despite undergoing three rounds of treatment, including various medications and injections, his symptoms lingered. Feeling defeated, he turned to herbal remedies.

Speaking with DevReporting during a telephone interview in February, Muhammed Sani, a resident of Kaduna also narrated his struggle with recurring malaria.

“After the hospital diagnosed me, I was given some drugs, and I felt better after three days. But the malaria came back a few days later. I returned to the hospital and received injections. Even after the injections, it relapsed again within five days.”

Abubakar Nasir, a vegetable seller in Kano’s Yanlemu area, also shared his disheartening experience with recurring malaria bouts last year. When symptoms first appeared, he purchased medication from a pharmacy, following the pharmacist’s instructions to take three tablets twice daily for three days.

Although he initially recovered, the malaria returned after a brief respite. Nasir revisited the pharmacy, obtained another round of medication, and regained his health, only to face another relapse. “But because I could not afford to buy another set of drugs after spending over N5,000, I decided to live with it and manage to continue my trade because I must feed my family,” he told DevReporting.

Scary data

The life-threatening disease, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) is primarily caused by parasites transmitted to humans through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. While early symptoms could include fever and flu-like illness, chills, headache, muscle aches, tiredness, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; severe symptoms can include kidney failure, seizures, mental confusion, and coma, among others.

Experts at Pace Hospital, India, explain that malaria fever symptoms usually appear within two weeks (10–14 days) from the day of infection by a Plasmodium-infected mosquito, that is, malaria vector.

Common symptoms of malaria in pregnancy are tiredness, increase in body temperature, headache, nausea, vomiting and muscle pain while severe malaria can cause complications within hours to days from the initiation of symptoms, such as cerebral malaria, severe anaemia, decrease in blood sugar levels, pulmonary oedema and acute renal failure.

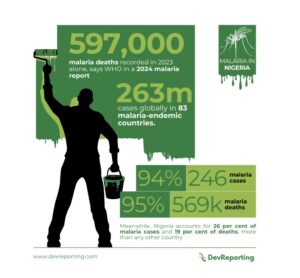

A 2024 malaria report by WHO paints a grim picture, explaining that in 2023 alone, there were an estimated 597,000 malaria deaths and 263 million cases globally in 83 malaria-endemic countries. Of the global malaria burden, the WHO African region carries a disproportionately high share with 94 per cent (246 million) of malaria cases and 95 per cent (569,000) of malaria deaths. Meanwhile, Nigeria accounts for 26 per cent (64 million) of malaria cases and 19 per cent (108,110) of deaths; more than any other country.

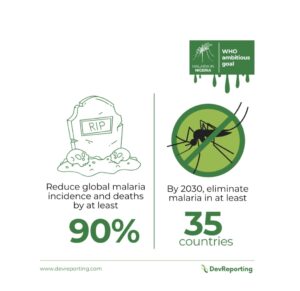

Though WHO set an ambitious goal to reduce global malaria incidence and deaths by at least 90 per cent and eliminate malaria in at least 35 countries by 2030, malaria remains a formidable public health challenge in Nigeria as the clock ticks toward the deadline.

What progress has been made?

Compared to 2022, there were eleven million more malaria cases globally in 2023, with Nigeria contributing a significant chunk. While 14 countries have been certified by WHO Director-General as malaria-free between 2015 and now, eleven other countries including Nigeria account for two-third of the world’s malaria burden.

Meanwhile, Nigeria with the highest burden of malaria has made several efforts to combat the disease through initiatives such as nationwide distribution of treated mosquito nets, public awareness campaigns, and collaboration with global health partners among others. Successive governments have also implemented several programmes and initiatives aimed at combating the disease.

The vision of the National Malaria Strategic Plan (NMSP) 2021-2025, for instance, is to achieve a malaria-free Nigeria while the goal is to achieve a parasite prevalence of less than 10 per cent and reduce mortality attributable to malaria to less than 50 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2025.

In 2013, the Nigerian authorities officially rebranded its ‘National Malaria Control Programme’ as ‘National Malaria Elimination Programme,’ signalling its ambition to achieve a malaria-free nation. Ten years down the line, the statistics tell a worrying story.

Again, ex-President Muhammadu Buhari, in August 2022, inaugurated the End Malaria Council, to mobilise funds, promote malaria elimination initiatives, and enhance the quality of life and wellbeing of Nigerians. However, a year later, Nigeria continued to bear the highest malaria burden globally.

With just five years left until the Global Technical Strategy (GTS) for Malaria 2016–2030 target; Nigeria’s position as the country with the highest malaria burden globally raises serious concerns. Recall that the GTS calls for a reduction in malaria case incidence and mortality rate of at least 40 per cent by 2020, 75 per cent by 2025, and 90 per cent by 2030.

Challenges

A major challenge hindering eradication of malaria is funding. In 2023, global funding for malaria control and elimination totaled $4 billion across 90 countries, showing a slight decrease from $4.1billion in 2022. As expected, WHO African Region received 75 per cent of this funding, owing to its high malaria burden. The amount made available to fight the disease falls short of the estimated $8.3 billion needed globally to meet the GTS targets by 2023.

Beyond funding, malaria-endemic countries, according to WHO, continue to grapple with fragile health systems, weak surveillance, and rising biological threats, such as drug and insecticide resistance while conflict, natural disasters, climate change and population displacement in many areas are exacerbating the already pervasive health inequities faced by people at higher risk of malaria.

This includes pregnant women and girls, children aged under 5-years, indigenous peoples, migrants, persons with disabilities, and people in remote areas with limited healthcare access.

Experts speak

A medical practitioner, Serah Agi, attributed the increasing resistance to malaria drugs to widespread self-medication. She explained that many Nigerians, especially those without health insurance, often buy over-the-counter drugs without consulting a doctor.

“Proper diagnosis ensures the right prescription,” she said, adding that taking over-the-counter medication can result in overuse, inadequate treatment, or incomplete treatment.

She added that some patients fail to follow prescriptions, skipping doses or stopping medication as soon as they feel better. “Medicine can heal, but it can also cause harm when misused. Poor compliance is very detrimental to one’s health.”

Highlighting factors contributing to Nigeria’s high malaria burden, a lecturer at the Department of Community Medicine, Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, Auwal Suleiman identified the environment as a major factor, noting that mosquitoes thrive in Nigeria’s warm, humid climate, while the outdoor lifestyle of many Nigerians further increases exposure to mosquito bites.

He noted societal complacency, saying, the widespread nature of malaria has led many to accept it as inevitable. “The drive for collective action against malaria is weak because people have gotten used to it,” the doctor said, adding that climate change, with its warming temperatures, is another contributing factor, creating favourable conditions for mosquito breeding.”

Dr Suleiman, who is also a fellow of the Nigeria Malaria Modelling Fellowship identified the state of healthcare in Nigeria as playing a major role. According to him, many malaria patients lack access to proper diagnosis and treatment. “Some of these issues are the ones contributing to the malaria burden,” he noted.

Despite the challenges, he expressed optimism that malaria elimination in Nigeria is possible, drawing inspiration from countries like Egypt that have achieved successful eradication of the disease. According to him, Egypt overcame malaria through concerted efforts, despite having a supportive environment for mosquitoes and a large population.

While he commended existing initiatives, such as the distribution of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), preventive drugs for pregnant women, and seasonal malaria chemoprevention for children, he pointed out significant gaps in implementation, saying, “only about 60 per cent of households have ITNs, and not all those who have them use them while many pregnant women also miss out on preventive malaria drugs during antenatal care.”

The expert therefore urged the Nigerian government to intensify its investment in malaria control programmes, emphasising the need for improved funding and strategic implementation.

“We are already spending significant amounts on malaria, but we must scale up the resources because the losses we incur due to malaria far outweigh our current investments. We cannot keep focusing solely on protecting people while mosquitoes continue to flourish. Interventions like indoor residual spraying, environmental management, and the destruction of mosquito breeding sites are crucial. Though, these interventions are expensive due to the cost of chemicals and the manpower required.

“They also demand community buy-in to ensure effective implementation. That is where the issue of funds comes in, if we are able to mobilise more funds to the malaria elimination programme, then, we can begin to look at some of these costly interventions that have a very good impact against malaria,” he exolained.

Underscoring the importance of community engagement in malaria elimination efforts, Dr Suleiman pointed out that countries that have successfully eradicated malaria relied heavily on strong community participation.

“Currently, malaria control in Nigeria is often seen as a government-driven initiative, but this needs to change. People must understand their critical role in the fight against malaria. Community ownership, mobilisation, and collaboration with civil society organisations and development partners are essential to achieving the desired outcomes.

“The government alone cannot win this battle. Success requires a unified effort from all stakeholders involved. Only by working together can we achieve meaningful and lasting progress in the fight against malaria,” Dr Suleiman stressed.

The Director of the Global Health Group at the University of California, San Francisco, Richard Feachem, who co-chaired a review of malaria eradication commissioned by the Lancet medical journal said, “For too long, malaria eradication has been a distant dream, but now we have evidence that malaria can and should be eradicated by 2050. We must challenge ourselves with ambitious targets and commit to the bold action needed to meet them.”