In the last five years, about 1,800 of over 3,000 academic staff of the University of Lagos (UNILAG), Akoka, representing almost 60 per cent, resigned their appointments from the tertiary institution in their quest for greener pastures, DevReporting reports.

Only 1,200 lecturers, including professors, senior, and junior academic staff, are currently on the university’s nominal roll. Yet the Vice-Chancellor, Folasade Ogunsola, a Professor of Medical Microbiology, said “the number keeps changing rapidly.”

However, the Nigerian government seems unconcerned by this significant threat as successive administrations have continued to grant approvals for new ones.

Mrs Ogunsola, who spoke in an exclusive interview with DevReporting, said the figure is now being supplemented by adjunct staff.

“Even at 3,000, we were not enough. So, you can imagine the situation now with this acute shortage,” she lamented.

This newspaper’s findings revealed that the situation is similar across Nigeria’s universities, polytechnics, colleges of education, and monotechnics, as many academic and non-academic staff have migrated abroad for the golden fleece.

The exodus of lecturers from UNILAG mirrors a national trend popularly referred to as the Japa syndrome, which describes the mass emigration of highly skilled professionals such as doctors, lecturers, information technology experts, bankers, and teachers.

Nigerians’ emigration to other countries has increased in recent years, largely due to poor economic conditions, high inflation, low wages, inadequate infrastructure, insecurity, and limited career prospects back home. As a result of this trend, Nigeria has lost a substantial number of experts, with many skilled persons leaving for countries offering better working conditions and pay.

Grim statistics

Data from the Migration Information Data Analysis System (MIDAS) of the Nigeria Immigration Service (NIS) indicated that in 2022 and 2023 alone, a total of 3,679,496 persons emigrated abroad legitimately.

The breakdown of the statistics indicated that 2,115,139 persons left Nigeria in 2022 while 1,574,357 Nigerians emigrated in 2023.

This data only speaks to those who left legally through the border posts, but there have constantly been many others who take the unusual routes through the deserts and the ocean to get to Europe and other parts of the world.

Read Also: Nigerian university VC leaves office over sex scandal as acting successor resumes

Nigerian experts including lecturers and medical practitioners, through their umbrella bodies such as the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) and the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA), have consistently lamented poor welfare packages, dearth of facilities, erratic power supply, and dilapidated infrastructure, among other challenges.

Government unconcerned

Despite the acute shortage of staff in the existing tertiary institutions, the Nigerian government has continued to establish new ones, a situation described by experts as unconscionable.

Between 2011 and 2012, former President Goodluck Jonathan approved the establishment of 12 new federal universities, while his successor, Muhammadu Buhari, established about 30 tertiary institutions between 2015 and 2021, including 11 universities, nine colleges of education, and 10 polytechnics.

On his part, President Bola Tinubu’s barely 2-year-old administration has approved 67 new tertiary institutions comprising 22 universities, 33 polytechnics, and 12 colleges of education. Mr Tinubu named one of the polytechnics after himself.

It should, however, be noted that these institutions include existing ones which have now been taken over by the federal government, such as the Tai Solarin University of Education, Ijagun, Ogun State; Nok University, Kachia, Kaduna State, which is now to be known as the Federal University of Applied Sciences, among others.

Universities’ proliferation

In his efforts to properly situate the problems facing Nigeria’s university system, a former Vice-Chancellor of University of Ibadan (UI), Olufemi Bamiro, in his contribution to a treatise on “NUC at 50” (a festschrift in celebration of the National Universities Commission at 50), traced the growth of universities in the country.

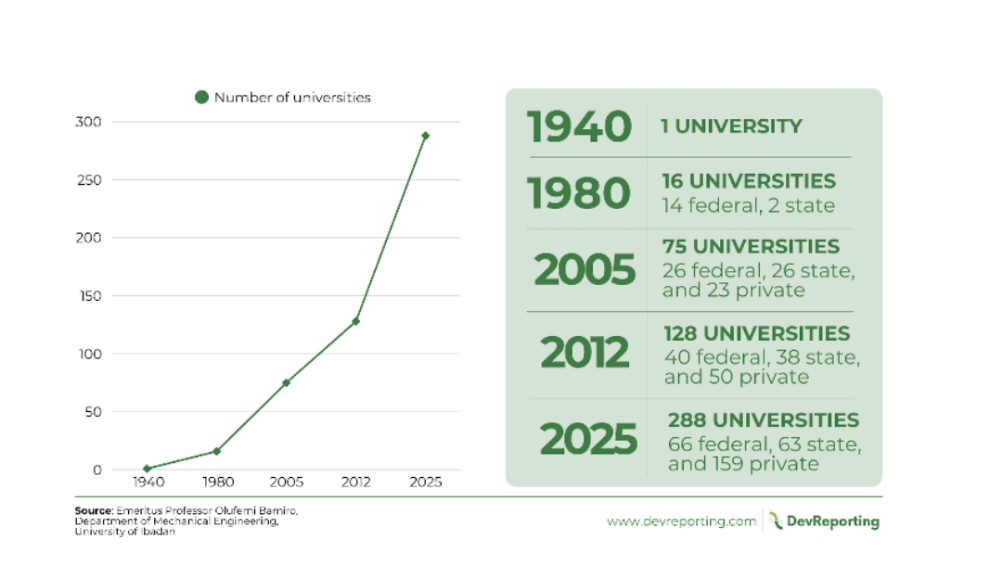

According to the professor of Mechanical Engineering and former Pro Chancellor of Tai Solarin University of Education, Ijagun, Ogun State, Nigeria had only one university as of 1940, but grew to 16 in 1980 with 14 owned by the federal government and two owned by the state governments.

Between 1981 and 2005, the number of universities in Nigeria grew to 75 with federal and state governments having 26 each while the private ones were just 23.

However, between 2006 and 2012, the number increased geometrically as private universities grew to 50 while those owned by the federal and state governments were 40 and 38, respectively.

Today, the figure is now more than doubled, with private, federal, and state universities standing at 159, 66, and 63, respectively, totalling 288.

But while the number of universities has continued to increase incredibly, the human resource capacity of these institutions has been falling steeply.

Staffing challenge

To show the connection between improved workers’ welfare and staffing strength in the university system, Mr Bamiro noted how the 2009 FGN-ASUU agreement encouraged more Nigerians to take up jobs as lecturers in the universities.

Read Also: Alleged Sex Harassment: Group insists on FUOYE VC’s suspension, wants governing council dissolved

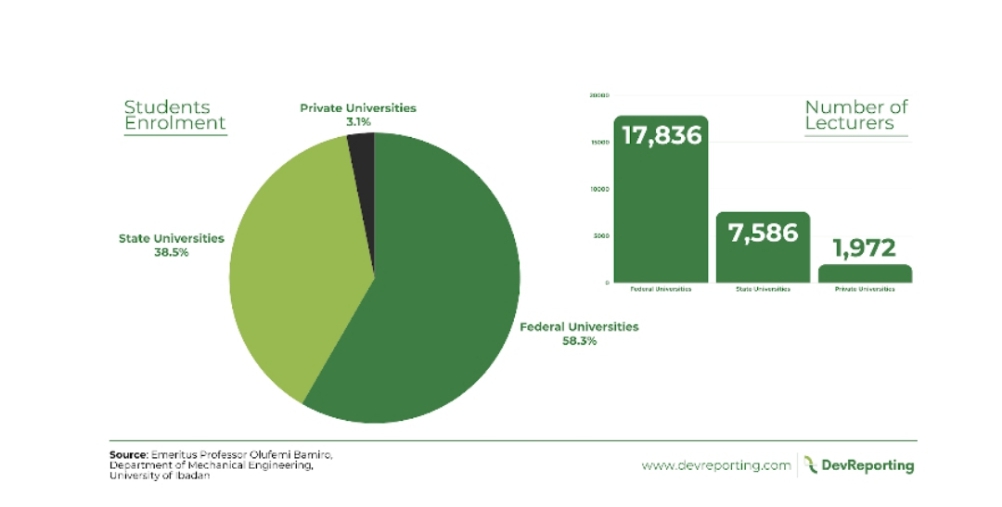

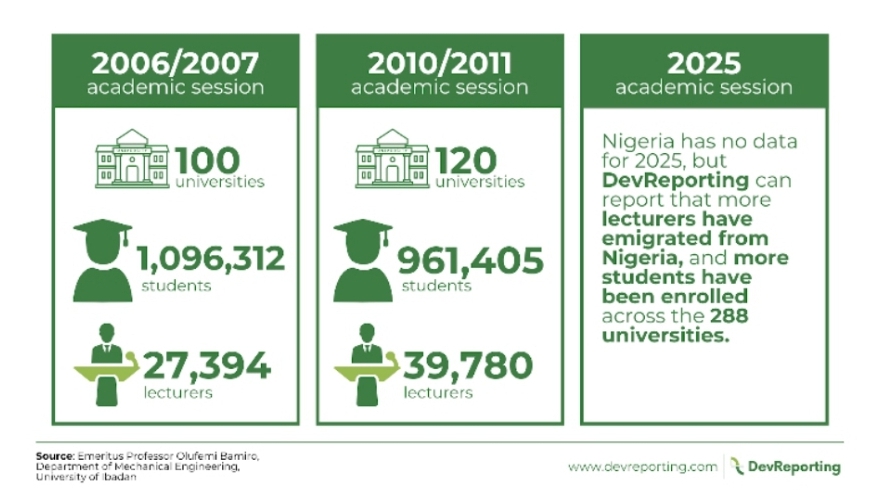

According to statistics provided by the scholar, as of 2006/2007 academic calendar year, with about 100 universities, and a total student enrolment of 1,096,312, across the federal, state, and private universities, Nigeria had 27,394 lecturers in all the universities.

The data further revealed that the federal universities that had 58.3 per cent of student enrolment also contributed a total of 17,836 lecturers, while the state universities that had 38.5 per cent of student enrolment had only 7,586 academic staff. For the private universities that contributed only 3.1 per cent of student enrolment, there were only 1,972 lecturers.

Quoting the then Executive Secretary of NUC, Peter Okebukola, a Professor of Science Education, Mr Bamiro said, of the 27,394 academic staff, those on the professor/reader cadre constituted just 5,483, amounting to 20 per cent; those on the senior lecturer cadre constituted 6,475, amounting to 23.6 per cent, while those on lecturer one cadre constituted 15,436, amounting to 56.4 per cent.

“Computation using current approved student/teacher ratios, however, indicates that the Nigerian University System requires a total of 34,712 academic staff for effective course delivery across the disciplines,” Mr Okebukola was quoted to have said.

To achieve an improved staff-student ratio based on the student enrolment figure and the university staff strength as of 2007 academic session, Mr Bamiro said Nigerian universities would require an additional 7,318 lecturers to increase the figure to 34,712.

Meanwhile, as of 2010/2011 academic session, with just about 120 universities but a reduced student enrolment figure of 961,405, the number of lecturers increased to 39,780, leading to improved average lecturer-student ratio of 1:24.

“The staffing situation improved significantly from 27,394 in 2006/2007 session to 39,780 in 2010/2011 session for reasons not far removed from improvement in staff salaries, which has enhanced staff attraction and retention in our depressed economy. At the level of staffing in 2010/2011, the global staff/students ratio was a healthy 1:24 compared to 1:37 in 2006/2007, excluding the sub-degree programmes,” the professor wrote.

But while experts had expected the situation to improve, the government’s failure to review the agreement entered into with ASUU and other university workers’ unions for more than a decade left many university staff demoralised. The degenerating economic situation further worsened the condition of these workers, who had no choice but to flee the country.

While lecturers are leaving the country in droves, the enrolment in the universities has continued to increase rapidly as the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) has been recording high turnout of applicants for its Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME), the entrance examination into the nation’s tertiary institutions.

Ahead of the year 2025 UTME, JAMB said more than 2 million candidates have registered, indicating more applicants than the tertiary institutions’ carrying capacities.

UNILAG’s precarious situation

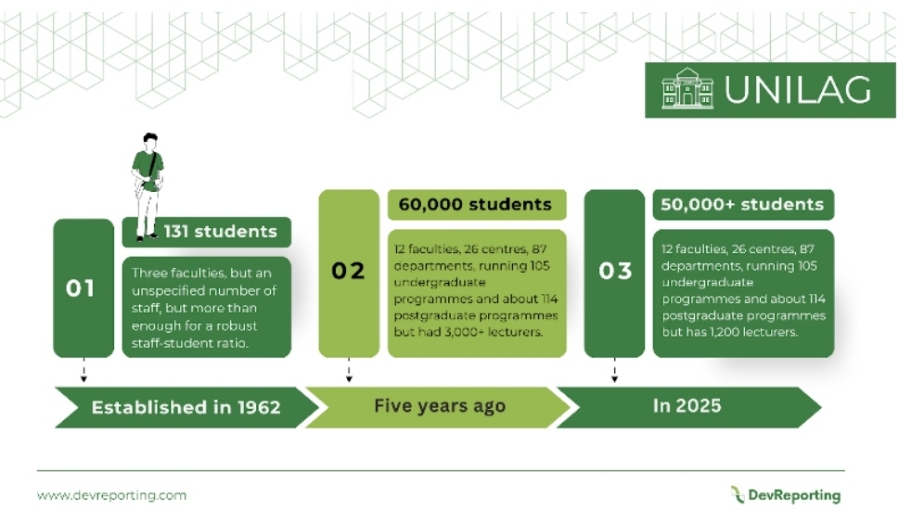

Founded in 1962, UNILAG is one of Nigeria’s first-generation universities. It is ranked second in Nigeria and falls within the 1001-1200 bracket out of over 2,000 institutions worldwide, according to the 2025 Times Higher Education World University Rankings released in October 2024.

From a modest intake of 131 students when the institution began in 1962, enrolment at the university has grown to over 50,000, including students in the Distance Learning Institute (DLI).

The university, which prides itself as the university of first choice and the nation’s pride, currently has six institutes, more than 20 centres, and 12 faculties.

DevReporting gathered that UNILAG has 87 departments (excluding newly unbundled ones awaiting NUC approval), offers 105 undergraduate programmes and 144 postgraduate programmes across multiple disciplines on its three campuses in Akoka, Yaba and Idi-Araba.

Despite its robust academic offerings, UNILAG has struggled to maintain adequate staffing due to Japa. With over 50,000 students enrolled in about 250 programmes, the pressure on the remaining 1,200 academic staff has intensified.

The situation has also significantly increased the faculty-student ratio to as high as 1:60 against the global benchmark of 1:16.

Consequences

When confronted with the uproar against the university’s adoption of virtual learning mode for a whole first semester in the ongoing 2024/2025 academic session, the UNILAG vice-chancellor confirmed that the decision was partly due to major renovation works at the students’ hostels and the shortage of lecturers, prompting the institution to rely on adjunct lecturers from home and abroad.

“It (virtual learning) is not entirely a bad thing because some adjunct lecturers are international and highly competent. While many of our staff have left due to poor working conditions, adjunct lecturers bring valuable industry knowledge. However, they aren’t always reliable and can disappear when you need them the most,” she lamented.

Defending the decision to maintain virtual classes, the vice chancellor noted that virtual learning platforms are likely to continue even when students return to campus.

She said students would return to school in batches for their examination, saying the issue of logistics was carefully considered before the decision was made.

Though many students expressed frustration learning through the virtual option, DevReporting can confirm that a larger percentage of the students have already finished their examinations. Only 100 and 200-level students are still sitting their examinations.

“We are almost 400 in my class, but the zoom link could only admit 300. So if there is any network issue, you would be out of the class, or join the live streaming option, which is usually poor, possibly due to the technology being adopted. The lecturers will also insist on attendance, and these issues have posed serious challenges to us as students,” a student who does not want to be quoted for fear of sanctions, told DevReporting.

Way forward

Worried by the situation, the UNILAG vice-chancellor said the university has made submissions on the issue of recruitment for consideration and approval. She noted that the process for recruitment is currently being coordinated by the Federal Ministry of Education.

But ASUU has consistently kicked against this practice of the ministry overseeing recruitment processes for the universities, describing it as a flagrant breach of the autonomy universities have to recruit staff, noting that nobody understands the recruitment of staff like the universities.

The ASUU National Vice President, Chris Piwuna, said universities, guided by their governing councils, should be able to handle staff recruitment more efficiently.

“What does the head of service or the ministry of education have in terms of knowledge of the university system? But now, the VCs are afraid to go to the ministry or the head of service because when they need just five staff, they go to these offices and come back with 35. Our universities need to operate within the laws of the universities, which are covered by the Autonomy Act. But as it is, honestly, it is quite sad,” he said.