Across four West African nations lies a century-old route from Nigeria to Côte d’Ivoire, crossed weekly by thousands in search of economic fortunes. Yoruba women from the Nigerian city of Ejigbo have turned this trail into a path for vast cultural exchange, heritage, and networking.

Rakiya Muhammad, Bird Story Agency

Every week, droves of Yoruba women from Nigeria journey through four countries to do business in the markets of Côte d’Ivoire. The 1,100-km road trip begins in the town of Ejigbo in southwestern Nigeria and takes them through Benin Republic, Togo, Ghana, and then finally, to the Ivorian capital of Abidjan.

“It was never in my thoughts that I would ever go to Côte d’Ivoire until one of my brothers came from there to take me,” said Rebecca Adebayo, a Yoruba woman who left Ejigbo for Abidjan fifty years ago.

Ejigbo is an ancient community in Osun West Senatorial District in the Yoruba region of southwestern Nigeria. Yoruba is one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria. The language is spoken by at least 30 million people.

The journey to Abidjan

The story of Yoruba women looking for a brighter future and economic sustenance in Abidjan goes back several decades, when limited opportunities in Nigeria pushed women to engage in commercial trade in the French-speaking country.

In recent times, the exodus has persisted, weaving stories of migration into the everyday life of the quiet streets of Ejigbo. Although specific statistics are non-existent, a casual interaction with many Ejigbo people will show that most families in Ejigbo have multiple members in Côte d’Ivoire.

Figures from the official website of Osun State, in which Ejigbo lies, note that out of about 1.2 million Nigerians residing in Côte d’Ivoire since the 1900s until the present, indigenous people of Ejigbo town make up more than 50 per cent.

Coach bus companies have developed over the years to serve the demand for Nigeria-Côte d’Ivoire transport.

The Secretary of LABA International Transport, Opeyemi Aderanti, who has been with the company for over six years, confirmed that the number of female travellers outweighs that of men.

“Many travelers focus on business, and since women constitute the majority in trade, this may explain why the population of women migrants exceeds that of men. However, we do serve both male and female customers.” Aderanti said.

Recalling her first journey, Sewa Abidoye said, “When I first approached the Seme border in Lagos, my heart was pounding. I had never crossed an international border before, and the chaos around me was overwhelming.

“Crossing into the Benin Republic, I felt a rush of relief mixed with apprehension. The language changed, and the environment felt more foreign. I realised I was beginning a journey into unfamiliar physical and emotional territory.”

Sewa was mesmerised by the lush green landscapes and lively market scenes in Togo. The border crossing process was quicker in Ghana, where the air was filled with music and energy.

“When I finally arrived at the Côte d’Ivoire border in Noé, I felt both exhausted and excited. I looked around and saw people bustling with purpose and felt a sense of hope,” she said.

Typically, it’s a three-day journey on a coach bus. Small vehicles can make it within two days.

When Ms Adebayo embarked on the trip fifty years ago, it was by the sea. “There were no luxury buses in Ejigbo going to Côte d’Ivoire. When I learnt that we would travel by ship, I was afraid and skeptical about entering it, but I eventually summoned enough courage to board it,” she narrated.

Migration data

According to the Migration Data Portal’s regional data overview for West Africa, Côte d’Ivoire constitutes one of the top 10 migration corridors in West Africa and is the number one destination country for migrants within the region.

As of mid-2020, Ivory Coast was home to 2,564,857 migrants, constituting 9.7 per cent of the population. People move within the region partly because of a shared goal to strengthen regional economic ties through the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

In February 2025, ECOWAS launched the second phase of its Support for Free Movement of Persons and Migration in West Africa for economic growth projects. The EU-funded initiative is designed to promote the free protocol and movement of persons, goods, and services.

Policies such as the 2008 ECOWAS Common Approach on Migration helped lay a framework for West African women migrants to cross borders for economic opportunities.

A distinguished researcher in migration, gender studies, diaspora, and sociopolitical history, Olalekan Adebodun, meticulously traced the roots of the Ejigbo-Cote d’Ivoire migration back to the 1900s when a couple of Ejigbo indigenes traveled to Abidjan for trade and ended up earning a decent livelihood. Captivated by the stories of success of these early pioneers, other Ejigbo residents decided to follow the path.

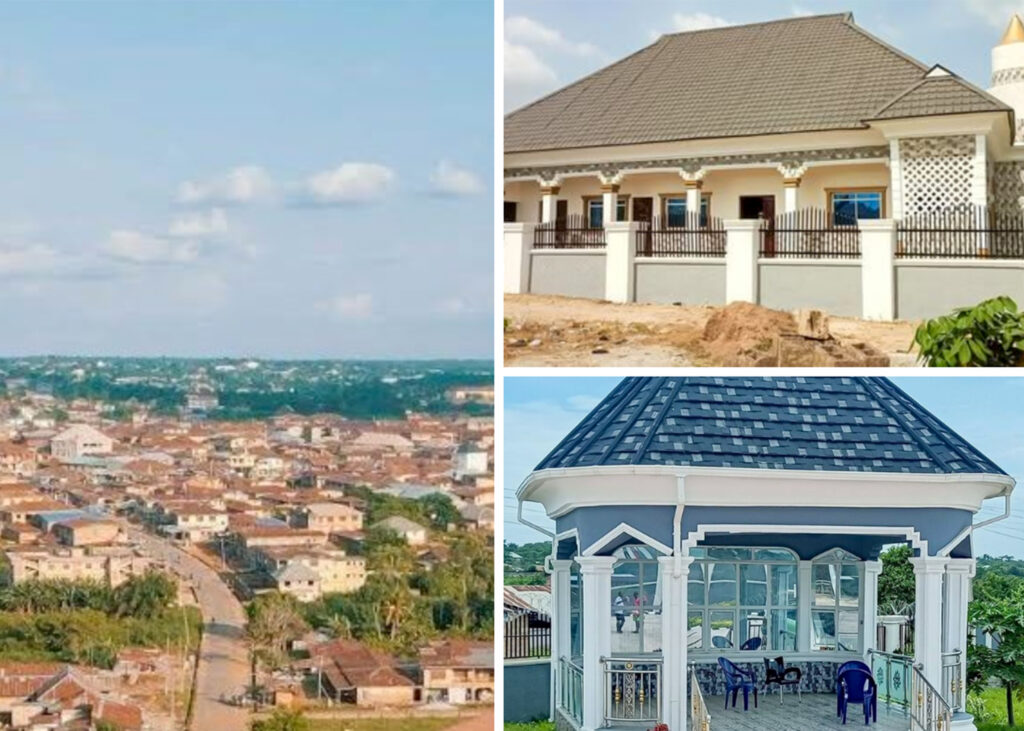

“During festive periods in Ejigbo, (Ejigbo) traders from Abidjan will come home with evidence of good fortune. They would build big houses to live in, or bring along big cars, putting on good clothes. Their contemporaries who migrated to other West African countries will tend to see that Abidjan is a home of fortune for Ejigbo people.

“The Ejigbo people had long decided to settle in Abidjan for business purposes, and this is what they are known for in Abidjan. Although there are Ejigbo people in other West African countries like Ghana, Togo, Burkina Faso, Liberia, and Benin, to mention a few, it should be noted that those in this category are few,” Mr Adebodun said.

He added that, by the early 1940s, wider opportunities for business ventures began to attract Ejigbo women to settle in Abidjan.

“This was made possible because, in the early phase of independence for the Ivorians, they had no opportunity to import from their neighbors due to the assimilation policy instilled in them by their colonial masters,” the historian added.

In Côte d’Ivoire, women from Ejigbo build new lives for themselves. Many start as traders, integral to local markets and economies. As they advance, they build a network that transcends ethnicity and language, sharing resources among themselves, offering advice, and creating growth opportunities.

Language barrier

Upon arrival, the Yoruba women encounter a language barrier – French. They turn to established female entrepreneurs for help. Ms Adebayo started by selling bananas, chewing sticks, and other items in front of her house.

“After two years, I could speak their language, and I started buying items in larger quantities and making more profit. I stopped selling bananas, and my new husband gave me some capital to start a business. In the market, I sold cosmetics and baby items,” she said.

Five decades later, she is a well-known entrepreneur among the Nigerian traders in Abidjan’s local markets.

A prominent Ejigbo indigene, Fatai Bello Oke, who was born and raised in Côte d’Ivoire, spoke of the dominance of Ejigbo women in the market. They own most of the major shops, making them the driving force of trade in Abidjan.

“Their influence extends globally, with many travelling to the UK, America, Italy, China, and other countries to import and sell goods in Côte d’Ivoire.”

A former ambassador to Nigeria in Côte d’Ivoire, Ifeoma Akabogu-Chinwuba, said, “Ejigbo women have played a major role in terms of ensuring peace and harmony among their people in Abidjan, and this was as a result of the special recognition that late President Félix Houphouët-Boigny gave to women in general that they should be respected in the country.”

Strengthening West Africa’s economy

Ejigbo women are a dominant force in Abidjan’s vibrant commercial hubs, selling everything from spinach (efo) to cassava. Sharing these food traditions strengthens an international bond between Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire, which in turn, strengthens West Africa.

Badirat Ayoni, born in Côte d’Ivoire to parents from Ejigbo, embodies this connection. As a second-generation migrant, she has balanced both cultures well.

Thanks to women like her, the culinary landscape of Ejigbo has undergone a fascinating transformation. The cherished Ivorian meal of attiéké (a fluffy couscous-like starch made of cassava) has found its way into kitchens back in Ejigbo, creating a vibrant fusion that reflects the interconnectedness of these communities.

When Ms Ayoni turned the key to her restaurant for the first time, she felt the thrill of a new beginning, a profound sense of achievement. Her aspirations had finally materialised.

“I felt a mix of disbelief and gratitude. After all the struggles, the sacrifices, and the long nights, seeing my vision of opening my own restaurant here in Ejigbo come alive was overwhelming.”

At that moment, she felt the heartbeat of the Ivory Coast pulse through every dish she served, bringing a piece of her adopted homeland to her community.

“Opening this restaurant, I wanted everyone to taste the heart of Ivory Coast right here in Ejigbo.”

Ms Ayoni is one of the many entrepreneurs who have harnessed their migration experiences to create economic opportunities, selling Ivorian local food in Ejigbo and catering to the local population’s mixed preferences.

“I sell attiéké in Ejigbo because the majority of people here are linked to Côte d’Ivoire, and attiéké is one of the major foods they all love to eat. It’s been over eleven years since I started, and I am the second person to start selling it in Ejigbo. I started selling when I noticed that many people demanded it and that one person couldn’t meet the demand. Later, many people ventured into the business, too.”

Abidjan vs Ejigbo: How business differs

Comparing her business in Abidjan and Ejigbo, the 57-year-old said both are moving well.

“If you have enough capital to invest in Nigeria, you will surely make it. But I travel to Côte d’Ivoire every three months because I still have business there. My children are there, selling for me. I take items like soft drinks to Abidjan and return with attiéké in large quantities.”

When asked why she returned to Ejibo, she said, “No matter how long you stay abroad, your home remains your home. I decided to return and stay in my hometown to explore.”

The migration has also influenced local languages. In Ejigbo, French is infused into English and Yoruba to create a colorful new type of creole.

Adeleke Folashade is one of many Ejigbo women who weave French into their conversations, embodying how cultures blend through trade and migration. She migrated to Abidjan three years ago and recently made a home visit to check on her family in Nigeria.

The 38-year-old businesswoman sells wholesale building materials in Côte d’Ivoire.

In Ejigbo market, goods from Côte d’Ivoire are on display. There are soap, aromatic spices, farming implements and colourful wax prints.

According to the leader of the market women of Ejigbo (iyaloja), Janet Oguntol, Ivory Coast is the economic pot of the people of Ejigbo, noting that products from Abidjan are strong, unique and affordable.

Abidjan returnees rebuild Ejigbo

Currently, a wave of Ejigbo women are returning to their homeland from Abidjan to bring more opportunities.

Ms Adebayo is a returnee who is investing in modern buildings, changing the infrastructural face of Ejigbo. Alhaja Aolat, a businesswoman in Ejigbo Market, spent decades in Côte d’Ivoire before returning home.

Many of these women have resumed their businesses with a fresh outlook. Whether they re-establish their former trade or launch new ventures, they are committed to revitalising the local economy. They introduce high-demand goods from Côte d’Ivoire, and their businesses flourish as they connect suppliers in Côte d’Ivoire with consumers back home.

The returnees are also revitalising villages, introducing new ideas and creating resources.

The Ejigbo central mosque building was built through contributions from Nigerians in Côte d’Ivoire.

The returnees have also built filling stations, churches, hotel and event centers, according to the secretary of Ejigbo Development, Tajudeen Oladipupo. He described the migration for greener pastures as good, adding that travelling is part of education and civilisation.

“Women are at the forefront of trading. Our women not only relocated to Abidjan, but they also traveled outside the Ivory Coast to trade. From Côte d’Ivoire to Dubai, Côte d’Ivoire to China, to America, and Côte d’Ivoire to the UK, and when they come home, they invest in Ejigbo.”

(Bird Story Agency)